Fourteen months after he launched an assault on the Libyan capital of Tripoli, Libyan National Army Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar stood on a podium on Saturday in Cairo next to President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi and Libyan House of Representatives Speaker Aguila Saleh to announce that he would be accepting an Egyptian-sponsored ceasefire and a initiative to restart political talks in the factional conflict.

The Cairo initiative consists of a military ceasefire and proposal for a renewed political process that came out of a Saturday meeting between Saleh, Haftar and several western and Arab ambassadors in Cairo. Following the meeting between Haftar and Saleh, the Cairo initiative was taken to Sisi for approval, according to an Egyptian official.

The initiative, a copy of which Mada Masr has reviewed, stresses the integrity and unity of Libya, the commitment to political talks initiated and supervised by the United Nations and set in motion by the Berlin conference in January, and an amendment to the long contentious Article 8 of the 2015 Libyan Political Agreement that formed the Government of National Accord, concerning the latter’s oversight over the future head of the Libyan Armed Forces.

The newly announced initiative marks a new direction in the management of the Libya crisis, where Moscow, alongside Cairo, have begun formulating a plan to offset Haftar’s influence following the collapse of the LNA’s western offensive.

Haftar, who has been an ally of Egypt, came to Cairo on Wednesday in a last-ditch effort to request military assistance to fight the GNA for territorial control in western Libya under the guise of fighting “terror groups supported by Turkey,” according to another Egyptian official briefed on the field marshal’s request, as his military patchwork of former Libyan Armed Forces officers, foreign mercenaries, local militias and Islamists was on its heels on the frontlines of Tripoli.

However, the one-on-one audience Haftar sought with Sisi never materialized, given what the Egyptian official describes as long-standing “frustration” with Haftar in Cairo’s ruling halls, which had looked at the LNA’s assault on Tripoli back in April 2019 with the backing of France, the UAE, Jordan and Russia with skepticism from the start. Instead, Haftar met with high-ranking Egyptian officials, according to a second Egyptian official.

On the same morning, forces aligned with the Government of National Accord — the political body Haftar has repeatedly tried to oust — took control of the remainder of the south of Tripoli, pushing the frontlines to the outskirts of Tarhouna, the last Libyan National Army holding from its once-expansive territory in western Libya.

The GNA’s victory was not crowned 180 km to the northwest of Tarhouna in Tripoli, where the government sits, but in Turkey, whose provision of ethnically Turkish Syrian troops on the ground and military equipment turned the tide of the war in the GNA’s favor. It was to Turkey that Fayez al-Sarraj, the head of the GNA’s executive authority, departed early on Thursday morning to meet Turkish President Tayyip Erdogan to celebrate his victory.

“We completely liberated Tripoli and its surroundings. Actually, this success is the victory of all of us,” Sarraj said from a podium in Ankara with Erdogan sitting nearby.

Erdogan used the press conference to announce that Turkey and Libya would advance exploration and drilling for oil in the eastern Mediterranean Sea, a stipulation of the memorandum of understanding the two sides signed in November that extended Turkey’s Exclusive Economic Zone to the coast of Libya.

On Friday morning, forces aligned with the GNA took complete control of Tarhouna after Haftar’s forces orchestrated a complete withdrawal to the east a day earlier, according to a former Libyan Armed Forces officer from Bani Walid, who is well informed of the situation inside Tarhouna. Haftar’s western offensive, launched with the assault on Tripoli in April 2019, had completely collapsed in under two weeks, and he watched the final scene of it unfold from Cairo. The GNA has since announced that it will mobilize to retake Jufrah in central Libya and Sirte in the oil crescent.

The relative ease with which Tarhouna was taken and the LNA-orchestrated withdrawal did not look to be in the cards even in the aftermath of the fall of the strategic Wattiyah Airbase in mid-May, when Egypt and the United Arab Emirates were already making arrangements for Haftar’s exit from his role at the center of the Libyan arena.

A third and fourth Egyptian official told Mada Masr in May that any security cooperation with the beleaguered general would be strictly for Egypt’s national security interests. Egypt, the officials made clear, was keen to prevent a power vacuum in the east of the country, especially given Cairo’s security concerns over the porous western border it shares with Libya.

Toward this end, Egyptian policy centered on two military aims: prevent Tarhouna from falling by continuing to provide the LNA with military reconnaissance information and keep militias away from the east of Libya.

But in Cairo, there was also an awareness that it was no longer in the driver seat. Beside Turkey’s influence in the west, Russia has emerged as the most important foreign sponsor in Cyrenaica, according to Jalel Harchaoui, a Libya analyst at the Clingendael Institute in The Hague.

“The Russian-made warplanes that appeared last month in Jufrah, along with the almost 3,000 Russian mercenaries still stationed in Libya, are simply vital for the anti-GNA factions in the east,” says Harchaoui. “The latter cannot survive without Russia’s military help. Within the Libyan theater, the Gulf states and Egypt aren’t able to stop Turkey. This situation gives Russia tremendous sway, which Moscow has every intention to use in the political realm now.”

A fifth Egyptian official told Mada Masr at the time that speculation over a potential Turkey-Russia deal meant Cairo must wait to see what its next moves will be. According to the fourth Egyptian official, there has been ongoing communication in recent days between Russia and Turkey, on one side, and Turkey and the United States, on the other. While the official understands there to be an agreement between Turkey and Russia that the forces fighting with the GNA will not move into the east of the country, Egypt has also reached out to the US to attempt to seek assurances that there is a line that won’t be crossed.

“There will be political negotiations with the east, but we must take Sirte and Juffra,” GNA Interior Minister Fathi Bashagha told Bloomberg on Sunday, suggesting there will be no advances further east after those cities are captured. “We need to prevent Russia from setting up bases in Sirte and Juffra.”

On Sunday night, Sarraj implicitly rejected the Monday morning ceasefire proposed by the Cairo initiative when he called the head of the Sirte-Jufrah operations room, urging him to continue the offensive to take the two cities.

Aware of Russia’s prominence in the negotiations, Egypt has initiated a flurry of diplomatic contacts with Moscow officials in the last week.

On Tuesday, Deputy Foreign Minister and Special Presidential Representative for the Middle East and Africa Mikhail Bogdanov and Egyptian Ambassador to Russia Ihab Nasr met to discuss developments in Libya.

And on Wednesday, Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry phoned Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov. According to the press release issued by the Russian Foreign Ministry, the officials “reaffirmed their common positions on the lack of alternatives to a political settlement in Libya and emphasized the need for the cessation of hostilities and the resumption of meaningful talks between the confronting Libyan sides. In this context, the ministers supported a program for overcoming the crisis in Libya, which was proposed by President of the Libyan House of Representatives Aguila Saleh. This program could become the foundation of intra-Libyan dialogue in promoting the development of the Berlin process.”

According to the accounts of Libyan and Egyptian officials who have spoken to Mada Masr in the last two weeks, the initial shape of Russia and Egypt’s “program for overcoming the crisis in Libya” is beginning to take shape.

A key pillar of Egypt and Russia’s plans is a political roadmap put forward by Saleh, the head of the Tobruk-based House of Representatives who was once a strong supporter of Haftar but is now vying for a larger stake in the political scene himself and is moving against the general. Saleh’s roadmap served as a basis for the Cairo initiative.

Saleh’s roadmap centered on restructuring and electing a new presidential council of three members from each of Libya’s historic regions, which then would form a new government, is the most visible component of this plan.

However, “for all of Haftar’s supporters, the determination that the field general is not a strong political and military leader has been made. But Haftar will not be sent out the door before Sarraj. Haftar and Sarraj will have to be out together,” the fourth Egyptian official says.

“If the Turks were to find it necessary to ask Sarraj to retire as a part of a political deal that would get Haftar away, then they would do it and Sarraj would not necessarily mind,” a Libyan political source close to Haftar says.

Haftar will not be fully pushed out of the picture immediately but will remain in Cairo indefinitely under close monitoring as he carries out a plan to form a political structure for the east, according to a high-ranking LNA officer close to the field marshal. The third Egyptian official says that Haftar will remain in Cairo for at least a few weeks before he will need to find a place to retire.

During Saleh’s visit to Cairo last weekend, high-ranking Egyptian officials impressed upon him that he should be less hard on Haftar, according to the third Egyptian official, who adds that, while Cairo had supported Saleh’s initiative, the high-ranking Egyptian officials informed Saleh that there would have to be “amendments,” without specifying what those “amendments” would be.

An informed Western official who spoke to Mada Masr on condition of anonymity acknowledged that the UK was in talks with Saleh but raised questions as to whether the parliamentarian could facilitate a political reconciliation all by himself.

The second Egyptian official, who spoke to Mada Masr ahead of Saleh’s visit to Cairo last weekend, agreed with this sentiment, saying that Saleh cannot be an alternative to Haftar. “He is too old, not anti-Islamist enough,” the official said. “With Haftar leaving the picture, the issue is now how can we make sure the Islamists don’t dominate Libya.”

Russia and Egypt are also considering turning to another key component of the Libyan political fabric to facilitate a political structure that sidelines Haftar: the network of supporters of former ruler Muammar Qadhafi.

In order to put together an anti-Islamist bloc, says the Libyan political source close to Haftar, Egypt will have to depend on former regime figures, many of whom live in Egypt and have strong ties with the Egyptian government. The fourth Egyptian official acknowledges that Egypt is open to some former regime figures, even if it is unclear if they can take a leading role.

In Haftar’s absence, the duties of heading the LNA will be shared with a leading general in the east, according to the second LNA source and the third Egyptian official. There doesn’t seem to be an agreement on who will take over the head of the eastern army yet, however. According to the LNA source, Major General Faraj Bughalia, a supporter of the former regime, is one of the names being considered for this position, for fear of disengaging Qadhafist elements loyal to Haftar and Russia. The Egyptian official says, however, that Abdel Razeq al-Nathuri, Haftar’s chief of staff, and Saqr Geroushi, the head of the LNA’s air force, are also being considered.

Haftar is also actively recruiting members of the former regime to be a part of the eastern political structure in the wake of the collapse of his western campaign, according to the high-ranking LNA officer close to Haftar and a former regime source who spoke to Mada Masr.

This calculus for Egypt would be compatible with Russia’s long-term play on former regime figures. While Russian-deployed mercenaries linked to President Vladimir Putin helped the LNA bounce back from their mid-2019 setback, Russia has consistently maintained contact with multiple players in Libya, including Qadhafists. They previously tried to facilitate contact with Qadhafi’s son, Saif al-Islam, according to a Bloomberg report in March.

“An aspect we know for certain about Russia’s thinking in Libya is its commitment to reinstating politicians, technocrats and military officers known for their loyalty to Muammar Qadhafi,” says Harchaoui. “These currents have been more or less neglected by all other foreign meddlers since 2011. But Egypt has harbored them.”

For Harchaoui, a turn to Qadhafist networks would be a welcome counterbalance or even a replacement to Haftar’s highly personalized brand of politics for Russia.

“The Kremlin is deeply committed to making sure Haftar wields less and less power. It deems Haftar too whimsical to be a dependable client. Moscow has always been profoundly skeptical about the field marshal’s 2019 decision to launch a frontal assault on Tripoli. By taking on an inordinate amount of risk in the west, Haftar caused the only security architecture in the east to risk collapse. The UAE did embrace Haftar’s bellicose adventure in April 2019, but Russia doesn’t like this kind of super-costly brinksmanship. The Russians are realists,” says Harchaoui. “By boosting Qadhafists and using their expertise, while continually negotiating with the pro-Haftar factions, the GNA and Turkey, Russia knows it can entrench its influence in eastern Libya in a unique and durable manner.”

“Russia plans to include members of the former regime in the political process,” says a Middle East-based foreign diplomat familiar with Moscow’s management of the Libyan file. “Some of them have good ideas, and they can be a part of the overall future of Libya. Russia has been talking to them as they have been talking to everyone.”

Russia is also making a play to make inroads with the GNA. GNA Presidential Council Deputy Ahmed Maiteeq visited Moscow on Thursday. At the close of the meeting with the Russian Foreign and Defense ministry officials, Maiteeq told reporters that the GNA has full faith that Russia will be an important partner in Libya’s stability.

The Russian Foreign Ministry’s press release on the meeting with Maiteeq placed an emphasis on the GNA’s release “as soon as possible and without preconditions” of Russian citizens Maxim Shugaley and Samer Sueifan who were arrested in Tripoli in May 2019 and accused of running a Russian troll farm aiming to influence Libya’s elections, as soon as possible and without preconditions.

“The Russian citizens remaining in prison in Tripoli is the main obstacle to the progress of mutually beneficial cooperation between the two countries,” the statement read.

According to the Middle East-based foreign diplomat familiar with Russia’s Libya policy, Moscow is confident that Sueifan and Shugaley will be released soon, as Russia’s contacts with the GNA have been expanded and there are parallel extensive talks happening with Turkish officials.

Egypt’s coordination with Russia shakes up the traditional alliances that have dominated the international dimensions of the Libyan conflict. That is not to say that Egypt will forego its existing ties, however.

“What’s remarkable here is how similar Egypt’s own calculus is to Russia’s at this juncture. In theory, one would assume Cairo just mimics Abu Dhabi, which has been its main benefactor since 2013. But that is not at all what’s been happening since Turkey intervened overtly in Libya,” Harchaoui says. “In Cyrenaica, Cairo cares about actual stability in the conventional sense and is proving much less absolutist than Mohamed bin Zayed on the Libyan file. This is not at all to say that the UAE is out of the picture. UAE’s combat drones have still been conducting airstrikes in Libya over the last few days. Plus, Abu Dhabi is a financial behemoth both Moscow and Cairo will seek to accommodate and please. But, now that Haftar’s Tripoli offensive has been crushed, the survival of the LNA and other institutions in Cyrenaica truly depends on the commitment of Egypt and Russia. The UAE, who could use a tactical pause, may have to accept that dynamic for now.”

Meanwhile, Russian and Egyptian cooperation to install a new power structure will face challenges.

For one, according to the first LNA officer, Haftar’s decline has opened room for the Federalist Movement in the east to gain momentum and court public opinion. The Cairo initiative’s emphasis on the integrity of Libya seems to be a direct rebuke to fears of disintegration.

But the bigger issue concerns how Russia’s relationship with Turkey will factor into the politics surrounding energy concessions in the eastern Mediterranean for Egypt.

While Turkey and Russia have supported opposite sides of the Libyan conflict, they have also shown a willingness to cooperate in Libya, as they have in Syria.

Despite there being a possibility of direct military engagement between the two sides, a former Turkish naval officer tells Mada Masr: “We have major economic ties. We cooperate in the energy area. We have security cooperation. There is defense industry cooperation. Russia will not let go of all this for Haftar.”

In early January, the two sides held talks and forced all warring parties to adhere to a ceasefire, with Russia applying pressure by withdrawing Wagner troops from the frontlines.

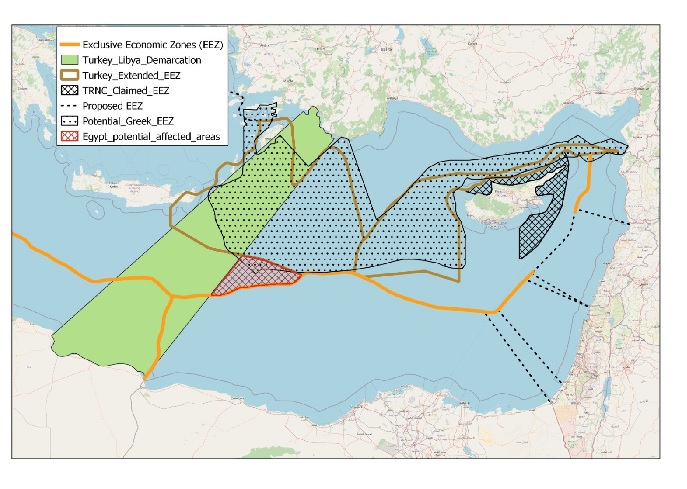

At the time, an Egyptian official expressed concern that the deal might signal that Russia had given the go-ahead to the maritime border demarcation agreement between Turkey and the GNA that would extend Turkey’s Exclusive Economic Zone to the shores of Libya on the basis that it would hamper work on the EastMed pipeline, the construction of which would have negatively influenced Russia’s control over the supply of gas to Europe.

The GNA and Turkey signed an agreement on maritime boundaries in the Mediterranean Sea in November alongside the deal that expanded the security and military cooperation that would prove vital in the GNA’s ability to fend off Haftar’s advance. The deal extended Turkey’s maritime EEZ to the shores of Libya, running through several areas in which Ankara is embroiled in disputes over energy exploration with other countries.

At the time, Egypt dismissed the deal as “illegal,” and Greece, which is an adversary to Turkey given historic tensions in Cyprus, said any such accord would be geographically absurd because it ignored the presence of the Greek island of Crete between the coasts of Turkey and Libya.

While Egypt outwardly condemned the November 2019 deal between Turkey and the GNA, officials at the Foreign Ministry and GIS were lobbying the presidency for a quiet acceptance of the deal, as it would have granted Egypt a sizable maritime concession (see map below) in these stalled maritime negotiations, according to third Egyptian official. However, this recommendation was not accommodated by the executive authority.

“In the criteria that Turkey uses for the delineation of the EEZs, Egypt will be entitled to a huge increase in its EEZ, almost as big as the territory of Serbia,” a high-ranking former Turkish diplomat tells Mada Masr.

However, the increase in Egypt’s EEZ must also compete with the larger political contest in the east Mediterranean as both Turkey and Egypt vie for the role of energy hub.

“Geopolitical conflicts are pushing Egypt and Turkey to compete with each other to become the east Mediterranean gas hub,” says Walid Khadduri, an oil and gas expert. “Turkey is expanding its military influence regionally, in order to put its hand on petroleum reserves in the areas it occupies militarily, further polarizing a hydrocarbon issue into a geopolitical polarization.”

Egypt invested significant political capital into securing an import deal with Israel that would be a first step in fashioning itself into a regional energy hub. Under the deal, Egypt began importing liquified natural gas from Israel that Egypt would then export through its existing LNG shipment facilities.

Erdogan is already looking to bolster his bid to oust Egypt from a position of supremacy even outside the scope of exploration off Libya’s coast. According to a European diplomat, Turkey has been in discussions with Italy, France’s rival for influence in Libya, about a gas deal using ENI’s Greenstream pipeline in western Libya.

This would threaten Egypt’s stated plan to use ENI’s pipelines in Libya. According to Khadduri, after the discovery of the mega gasfield Zohr, Egypt declared an intention “to export gas to Europe through a pipeline that would run from Zohr to Libyan gas fields operated by ENI, which also operates Zohr, and connect the Libyan offshore fields with an offshore gas line to Italy.”

When French President Emmanuel Macron and Sisi spoke on May 30, they addressed Turkish expansion into the Mediterranean, agreeing that Turkey should not be able to single-handedly control the Libyan matter of gas, an Egyptian official told Mada Masr. It was a sentiment also expressed after the fall of Wattiyah, according to the third Egyptian official, when beyond border security, Egypt’s concern was preventing GNA forces and Turkish troops from reaching the oil crescent.