Oversight, accountability, and governance of the security sector are essential ingredients to a capable and effective force, mitigating infractions and contributing to a learning environment that improves future practices.

Highlights

The security sector is equally subject to the law and oversight institutions as any other public agency.

Weak security sector oversight institutions inhibit security sector professionalism in Africa. Stronger internal and external oversight is an essential element of enhancing security sector effectiveness.

Security organs should construct institutional frameworks that nurture professionalism and a consistent apolitical posture.

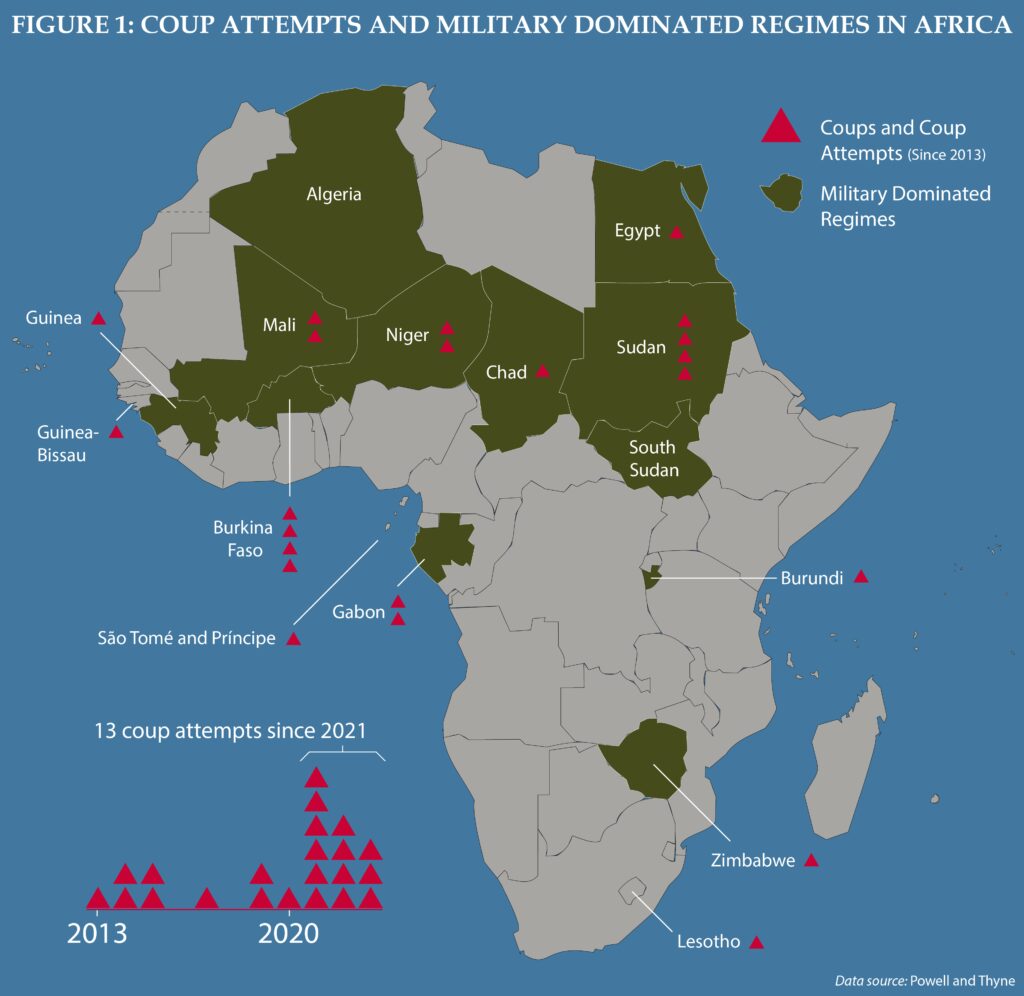

When security actors allow themselves to become politicized, they erode the credibility of security institutions among the population and can themselves become a security threat to citizens.A lack of strong security sector oversight institutions in Africa has hampered efforts to improve military professionalism, enabled corrupt officials, and hobbled defense and security forces on the continent. Nine military coups d’état in seven countries since 2020 underscore the continued politicization and lack of professionalism plaguing certain defense forces. In each case, despite pledging to return political power to civilians, the military juntas have repeatedly extended their timelines for political transition, exacerbating the economic strains on the citizenry. In Sudan, the unwillingness of the military to allow a democratic transition has resulted in an implosion of the security sector and state collapse.

African governments rank among the weakest in terms of arresting corruption in the security sector, which diminishes public trust in government and threatens national and regional security.1 Roughly half of all security sectors rated by Transparency International as facing critical or very high levels of risk of corruption are African.

“Effective security sector oversight helps ensure that the solemn responsibility of security actors to bear arms is used in the interests of society.”Illustratively, according to Afrobarometer surveys, more than 50 percent of respondents in Côte d’Ivoire, Eswatini, Gabon, Nigeria, and Togo place just a little or no trust at all in the military. Meanwhile, even higher proportions of respondents in these five countries felt corruption had increased over the previous 12 months, and more than 80 percent felt one risked retaliation for reporting corruption. More than 40 percent of respondents in another nine countries hold just a little or no trust at all in the military. These percentages are even higher for the police in many African countries where they are perceived to be among the most corrupt institutions.

Public accountability and transparency are key challenges for African security sectors. Out of 45 African countries that publish a budget document, 28 provide no actual expenditure document.2 Furthermore, there is little or no engagement over budgets between security sector and civilian leaders.

Many African countries continue to lack effective legislative oversight of the security sector, sapping security forces from fulfilling their mission. Without effective accountability of the security sector, impunity and unprofessionalism have flourished, degrading the capabilities of security forces. The engagement of security officials in illicit activities, abuses against civilian populations, and politicization further undermine the effectiveness of African security actors. This has directly contributed to greater instability and threats to citizen security.

The record of security sector reform across the continent remains checkered. In some cases, militaries have resisted reforms, curbing the effectiveness of oversight and accountability mechanisms.

Cases where the military holds either de jure or de facto political power present highly problematic situations. Political interference by defense and security forces effectively renders mechanisms of oversight and accountability toothless. When defense and security officials prioritize protecting their political agenda or those of ruling cliques mired in corruption rather than citizens’ security interests, security forces themselves become a threat.

Principles of Security Sector Governance

Security sector governance refers to the structures, processes, values, and attitudes that shape decisions relating to a country’s defense and security and their implementation in a democracy.3 Democratic security sector governance is based on the principle that legitimacy to govern derives from elected civilian leaders who then have the authority to set priorities for the security sector. Security actors, in turn, derive their authority from their subordination to this legitimate civilian leadership. The rule of law is a core element of democratic security sector governance, which is founded on the principle that no one is above the law.

“Upholding constitutional order entails performing security functions without violating the rights and freedoms of individual citizens.”Effective security sector governance requires a system of checks and balances where vibrant legislatures and independent judiciaries provide the necessary oversight to hold authorities accountable to citizens, including in the domain of defense and security. Effective security sector oversight helps ensure that the solemn responsibility of security actors to bear arms is used in the interests of society.4

Democratic security sector governance is also based on the principle of transparency. The role and rationale for security actors in providing citizen security should be clearly articulated. This builds popular support for the security sector while providing a basis to assess how well security actors are achieving their missions.

Challenges to Security Sector Governance in Africa

Africa’s security sector governance challenges stem from colonial legacies that shaped militaries to protect the ruling elites rather than citizens. At independence, the absence of a system of checks and balances enabled the interweaving of political, military, and economic interests. This process integrated the security sector into nascent political regimes and weakened prospects for oversight and accountability.5

The end of the Cold War brought a shift from a focus on regime security to citizen security. This paradigm shift broadened the range of actors with a role in security sector governance to include the judiciary, civil society, and the media.6 The reorientation of security to citizens accompanied the democratization of many countries in the early 1990s.

Nonetheless, the process has been subject to a range of challenges.

Shallow understanding of democratic control of the security sector. While most democratic constitutions provide for the subordination of security agencies to civilian control, military and civilian authorities do not always understand the extent and limits of this control. For example, former Malawian President Peter Mutharika tested the limits of civilian control of the security sector when he ordered the appointment and deployment of senior military and police officers through the State House. In one instance, the acting inspector general of police filed a petition in the High Court arguing that the president’s action involving the transfer of the Police Commissioner was not taken in the public interest but was instead victimizing a professional officer. The High Court annulled the transfer deeming it politically motivated.7

Civilian control of the armed forces is not equal to the direct command and control of the troops. Rather, civilian control refers to the process by which elected civilians set the strategic direction regarding the use of the security sector, and these civilian leaders are held accountable by the people.8

“Illegal orders to the military by politicians are precursors to corruption, oppression, and lack of professionalism, and can lead to greater politicization of security organizations.”The civilian head of state, who is usually also the commander-in-chief of the armed forces, is typically a leader of a political party. This double-cap can blur the line between objective nonpartisan civilian control of the security sector and the political interests of the head of state’s party. When the head of state issues politically motivated orders to the chief of defense or other officials, military commanders may be compelled to obey such orders out of fear of reprisal or a misunderstanding of the bounds of democratic control.

The legacy of the security sector’s integration with political regimes in Africa has complicated the separation of these domains in contemporary African politics. Illegal orders to the military by politicians are precursors to corruption, oppression, and lack of professionalism, and can lead to greater politicization of security organizations.

Politicization of security institutions. The law requires security organizations to discharge their duties as impartial civil servants of the public and the government. For this reason, security actors are not permitted to participate directly in political activities, although this does not restrict their right to vote. Any member of a security organization who wants to participate in active politics has the right to resign or retire.

Some security organizations on the continent have been heavily politicized to the point that security actors are more loyal to their patrons than to their institutions. Partisan behavior undermines the cohesion, effectiveness, and performance of security organizations. For example, some leaders in the Nigerian police were reported to have been appointed based on their political allegiances rather than ability.9 Accusations of favoritism and nepotism are rampant throughout Africa’s security sectors that eschew norms of meritocratic advancement.

The Uganda People’s Defense Force goes further. Ten seats in the Ugandan parliament are reserved for military representatives to advance the interests of the military within the legislature. The representatives are chosen from 30 nominees submitted by the president. It is the only permanent legislature in Africa with seats reserved for military representatives, though junta-led governments in Burkina Faso, Chad, Guinea, Mali, and Sudan also have military representatives in their legislatures.

Democratizing reforms in the 1990s witnessed many military leaders retiring from service to pursue politics. In some cases, these retirements were symbolic and the politicization of the security sector persisted. Zimbabwe presents a clear example of the continued political influence of the armed forces both under former President Robert Mugabe and his successor, Emmerson Mnangagwa. In other cases, such as Senegal, the defense forces have maintained a nonpartisan position and remained outside politics. This reputation is being tested, however, with the deployment of gendarmerie and police to apparently target the political opposition.

Erosion of military professionalism. When the defense and security forces become beholden to political barons rather than the public, their professionalism degrades. The erosion of military professionalism has plunged to such depths that it has resulted in officers claiming political power for themselves through coups d’état. The spate of coups and attempted coups in Mali (2020 and 2021), Chad (2021), Guinea (2021), Sudan (2021), Burkina Faso (twice in 2022), Niger (2023), and Gabon (2023) highlight the current low levels of military professionalism in these countries. This pattern of extra-constitutional actions demands a rethink of professional military education and international security cooperation in Africa.

Members of the military and law enforcement are required at all times to fulfil the duty imposed on them by law—serving the community and protecting all persons against illegal acts—consistent with the high degree of responsibility required by their profession. This in turn helps to ensure that the security sector remains accountable to their service mission.10

“When defense and security officials prioritize protecting their political agenda … [they] themselves become a threat.”Policing requires direct engagement with the public in the day-to-day lives of citizens, with direct implications for social progress and change.11 The regular interactions of police with the public increase the possibility of abuses when security forces lack professionalism. This is also a risk when the military is consistently involved in internal security operations.

Allegations of rape and sexual assault against the Malawi Police Service after they raided villages of suspected criminals at Nsundwe Market in Lilongwe in 2019 exacerbated the public’s perception of the police.12 Cases of corruption and abuse by police officers provide a blunt indicator of weak standards of professionalism in the security sector. Where perceptions of police corruption are high, it is little surprise that trust in law enforcement is low.13

Non-statutory forces in the security sector. Many African governments recognize informal security units such as community-based armed groups, vigilance committees, political party militias, or even national militias. At times, these units fill significant gaps and play a complementary role to law enforcement agencies. However, falling outside of established command and control or oversight structures, such groups can pose a security risk to citizens.14

Informal security groups are usually untrained and more prone to engage in abuse or excessive force. They may also be more vulnerable to politicization or manipulation by political actors. The now defunct Bakassi Boys in Nigeria, for example, took the law into their own hands and were feared more than regular criminals. Vigilance committees in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, have shown that where these groups exist alongside robust community and police oversight, they can be effective.15

Ambiguity in upholding the constitutional order. To uphold and protect constitutional order implies that the military must stay loyal to the constitution and legitimate government. However, the exact parameters of when and how the military can defend the constitution are not always straightforward, something that wily politicians may try to exploit.

The Malawi Defense Force’s mandate has been tested on several occasions. Perhaps most famously was following the April 2012 death in office of President Bingu wa Mutharika. His inner circle did not want then Vice President Joyce Banda to take over as required by the constitution. The Malawian military, in adherence to the constitution, helped to ensure that Vice President Banda became the next president as per the dictates of the constitution.

Upholding constitutional order becomes particularly salient in times of political uncertainty or when constitutional provisions are challenged by political actors. Such instances are not uncommon in Africa, where some elected leaders flout term limits and election results. This can be particularly complicated when political leaders act to rewrite the constitution to remain in power. At times, political leaders secure the approval of the courts for such controversial revisions, creating ambiguity around the parameters of the constitution and the role of the security sector in upholding them.

This was the case in Chad during 2018 when then-President Idriss Déby reformed the constitution to bar younger opponents from elections while simultaneously formalizing his ability to extend his time in power. Déby also deployed his presidential guard to intimidate political opponents.

Ultimately, upholding constitutional order entails performing security functions without violating the rights and freedoms of individual citizens, including political opponents of the ruling party.16

Balancing transparency and confidentiality in the security sector. Transparency is a fundamental principle of accountable governance. An opaque security sector creates an environment conducive to abuse and unprofessional conduct. Without information about the formulation and implementation of laws, policies, plans, and budgets, it is impossible to hold public servants accountable.

Confidentiality is necessary for sensitive matters of state security. Difficulties arise when the need for confidentiality is used to evade scrutiny by appropriate management authorities or citizen groups. Experience has shown that by developing trusted relationships with legislative committees or other oversight bodies, security organizations can retain a high degree of confidentiality in sensitive matters without compromising the principle of public accountability.

Entrenched corruption and enfeebled resource management institutions. Public finance management presents a problematic area within the security sector. The financial and administrative affairs departments of security organizations are commonly bureaucratic window dressing—severely understaffed and lacking the means to carry out their duties. Government auditors general often lack access to financial records. The resulting weak oversight of procurement contracts by defense and security ministries enables widespread corruption.

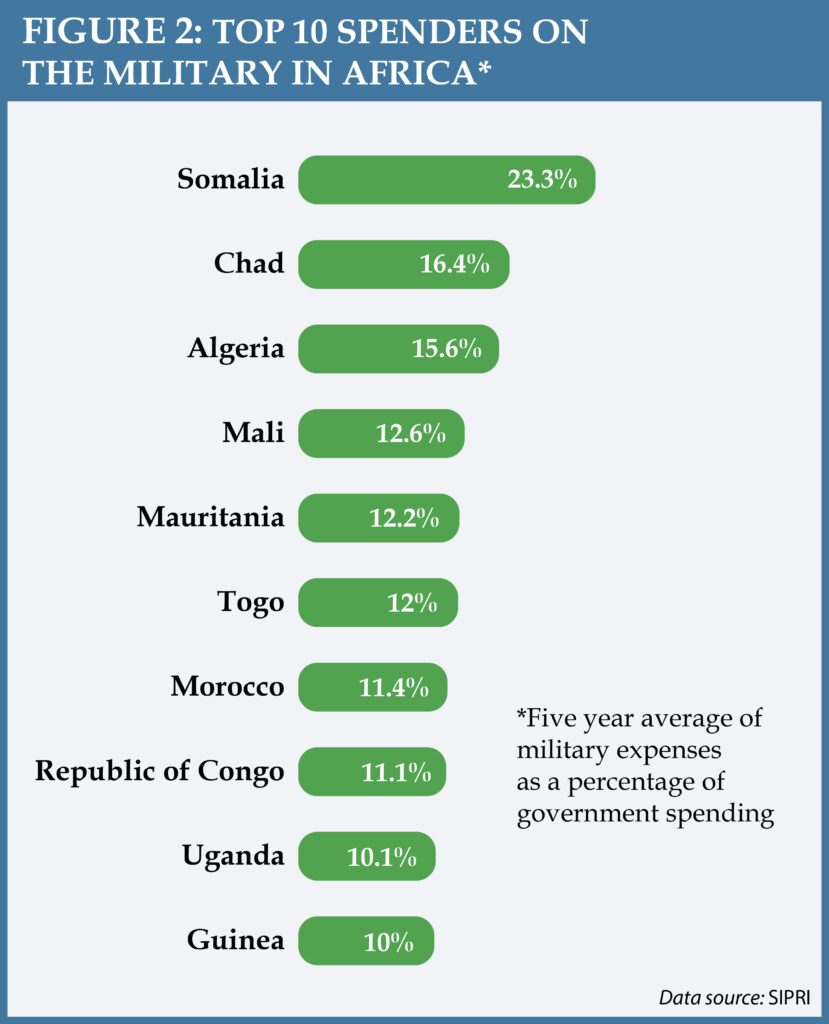

Some African countries have incurred mounting military spending without realizing significant improvements in citizen security and safety. Since 2018, 10 countries have averaged defense expenditures over 10 percent of government spending, with Somalia, Algeria, and Chad each averaging over 15 percent. While this may be warranted, these resources must be justified relative to other pressing requirements. Parliament holds the power of the purse and must approve budgets and monitor their implementation, even though legislative oversight of the security sector remains nascent in most African contexts.

Key Components of Civilian Oversight of the Security Sector

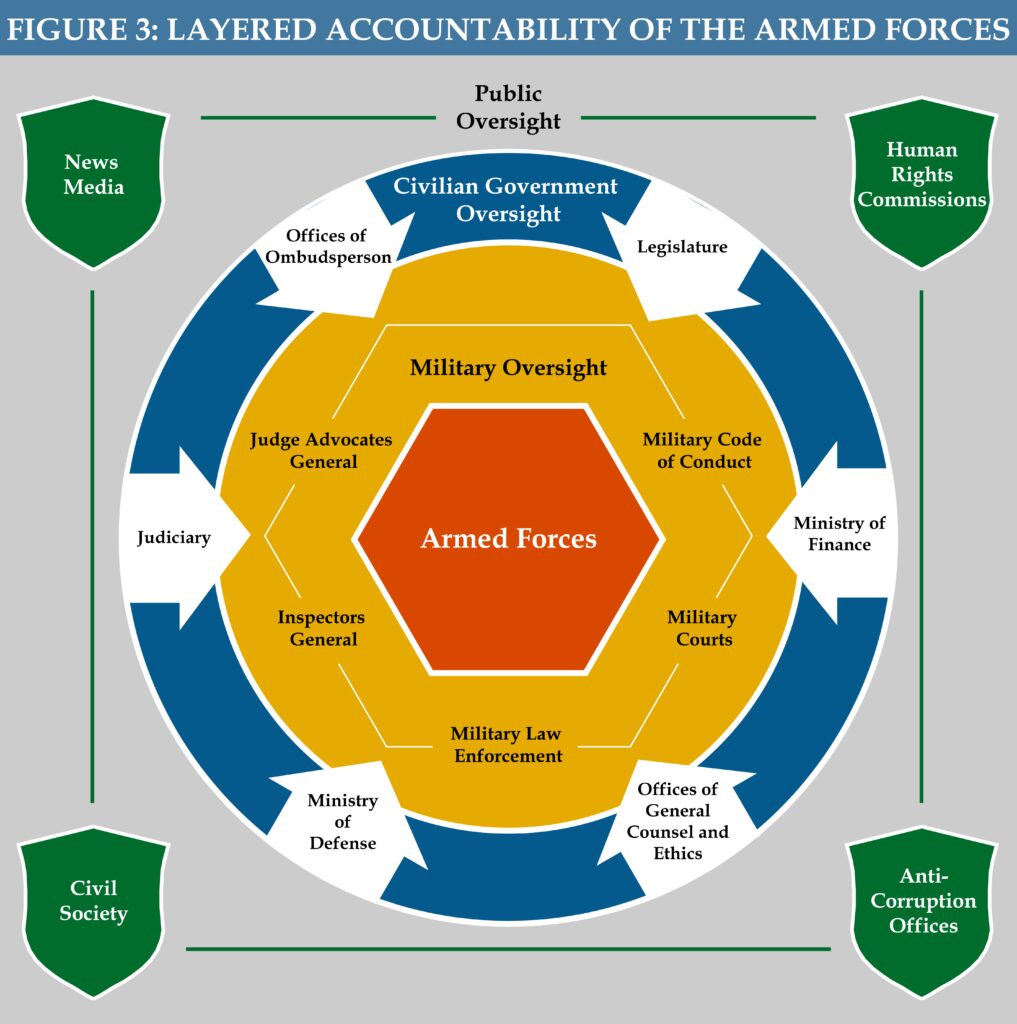

Accountability of the security sector entails that security organizations must be answerable to those institutions legally mandated to oversee their activities. It also means that oversight institutions must have enforcement mechanisms for breaches and compliance by security organizations. Accountability ensures that defense and security forces do not benefit from impunity due to their positions of power within society.

Accountability occurs through direct and indirect means. Direct accountability means security organizations must answer directly to the public they serve. Parliamentary committees on defense and security and the offices of ombudspersons fill that function in practical terms. Indirect accountability is when politicians and bureaucrats are held accountable by the public for the actions of security organizations.17 For example, in Ghana, Kenya, Senegal, and Zambia enshrining the role of civilian oversight bodies in the constitution initiated a process of empowering civilian leaders to review the management of the security sector.

Following suit, the number of countries with formal provisions for legislative oversight bodies, such as defense and security committees, is on the rise. The Network of African Parliamentarians Members of Defense and Security Committees (REPAM-CDS) is an African forum for debate on defense and security issues open to membership by parliamentarians serving on defense oversight bodies. Established in 2018, REPAM-CDS boasts membership from 26 countries.

With mandates that include budget control, approvals of troop deployments, equipment procurement, security policy, and personnel issues, legislative committees require staff with technical expertise and experience to help elected officials meaningfully execute their duties. Developing civilian expertise on security issues helps to build trust with their security sector counterparts and plays an important role in the receptivity of their findings.

Ombudspersons, human rights commissioners, and anticorruption agencies—as seen in Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Nigeria, and South Africa, for example—are means of horizontal accountability by which civilians can contribute to security sector governance.18 Cases of defense corruption, embezzlement, and money laundering are often brought to public attention by civil society organizations.19 For instance, in 2020, the independent anticorruption body in Burkina Faso brought evidence against former Minister of Defense Jean-Claude Bouda, leading to his arrest.

The media also have a key role in the oversight of the security sector by raising awareness of the responsibilities and performance of security organizations in the discharge of their constitutional functions as well as drawing attention to areas of reform.20 The media, human rights organizations, and security policy analysts can track behavior, draw attention to deviations from national and international law and good practices, and make suggestions on ways of improving accountability. Encouraging press coverage of the security sector and empowering civil society organizations to engage with security sector officials helps to connect defense and security forces to the broader population and strengthens their ability to serve communities.

“Oversight … [holds] accountable those responsible for abuses, ultimately strengthening the security sector by mitigating losses and improving future procurement practices.”Robust military oversight can contribute to military effectiveness. A 2020 Nigerien government audit revealed that almost 40 percent of $312 million spent on defense procurement contracts had been lost.21 The report found numerous cases of unfair and fictitious competition and concluded the government had lost roughly $120 million to fraud. The audit became public knowledge thanks to the tenacious reporting of local journalists. Following the reporting, four civil society organizations filed paperwork in court to pressure the government to open an inquiry which it did, resulting in both civil and criminal investigations.

The audit, press reporting, civil society filings, and judicial process each represent important steps in the oversight and accountability of the security sector. Collectively, such oversight processes of procurement contracts help hold accountable those responsible for abuses, ultimately strengthening the security sector by mitigating losses and improving future procurement practices.

Improving Security Sector Governance through Oversight and Accountability

Oversight and accountability of the security sector ensures that government can manage security organizations effectively and efficiently. In doing so, it builds citizen trust in the defense and security forces.

Professionalism of the security sector is guided by the principles of subordination to democratic civilian authority, allegiance to the constitution, commitment to political neutrality, and an ethical institutional culture. The following are key recommendations to strengthen oversight and accountability of the security sector in Africa.

“Coups are not solutions to the shortcomings of delivering public goods to the people …[or] an antidote to neocolonialism.”Condemn and punish military putschists. Military coups should be uniformly condemned and the plotters held accountable. Coups d’état have a domino effect such that a successful coup significantly increases the probability of subsequent coups in that country and its neighbors.22 Therefore, if the putschists act with impunity, the trajectory of military takeovers will continue.

Putschists usually promise to reverse the tide to provide socio-economic dividends to citizens. Yet, the track record of coups is that they increase instability and corruption while undermining economic development. Coups are not solutions to the shortcomings of delivering public goods to the people. Neither are military coups an antidote to neocolonialism. The stratagem of military coups is the very antithesis of a democratic culture that upholds civilian control of the military.23

Uphold and reinforce the separation of politics and security. Each African country should have clear laws that prohibit political actors from directing members of the security organs to take actions of a political nature intended to benefit the incumbent party or undermine the interests of opposition parties. These laws should specify stiff penalties for those that do so. Citizens should also be legally empowered to petition the courts when security actors are deployed in political actions.

Defense and security organs should adopt a clear code of conduct to assimilate ethical values into the culture of security services while reinforcing norms of constitutionalism, integrity, service, and respect for human rights and democratic principles. These norms and principles, democratic security sector governance, and civil-military relations must be reinforced by a robust and sustained training program for security professionals at all levels and stages of their careers.

This should be accompanied by outreach and training for citizens so that there is more popular awareness of the stark separation in roles of military actors and political authorities under democratic security sector governance.

Provide technical support for legislative staffers on defense and security committees. Legislatures should strengthen their oversight of national security policies, transparency and accountability in the procurement of security materiel, merit-based recruitment and promotion, and the modernization of the defense and security sector. Legislators should codify the roles and responsibilities of political actors vis-à-vis the security sector, including the role of the legislature. Legislation for the oversight functions of the government, the chain of command within different security agencies, the mandate of each security organ, and the broad democratic principles governing security organizations should all fall under legislative purview.24

Incapacity of civilian authorities to oversee the defense and security sector is a common constraint for achieving democratic security sector governance in Africa. Instituting a regular schedule of security briefings for elected officials to elevate their understanding of the security sector will help them better oversee the activities of the security sector while building trust with the military and police. International partners could support this by providing training for legislatures in military affairs management and oversight in democracies.

African militaries could share with one another their lessons learned and best practices in security sector governance. A center of security sector excellence within professional military education institutions might facilitate such cross-government exchanges.

Strengthen the independence of oversight institutions. Independent oversight institutions such as ombudspersons and human rights commissions should discharge their constitutional roles to ensure that security organizations uphold constitutionalism and the rule of law. National constitutions should guarantee the writ of parliamentary and independent oversight bodies to safeguard citizen interests, mediate the excesses of security actors, and help enforce the law.

This is particularly important for law enforcement given its role in the everyday lives of citizens. The police must be impartial in their enforcement of the law. Given their proximity to the public, police should establish complaints commissions where aggrieved parties can lodge their concerns.

Governments should also establish independent lines of funding and staffing to ensure oversight bodies have adequate resources to accomplish their constitutional mandates. This includes support for independent offices of inspectors general within military and police agencies.

“Upholding constitutional order entails performing security functions without violating the rights and freedoms of individual citizens.”Invest in transparency, oversight, and accountability in the security sector’s public finance. Multitiered institutional investments should be made to enhance security sector resource management and expenditure oversight. Governments should establish robust internal and external oversight mechanisms of the defense and security organizations to ensure funding is appropriately expended toward national security interests. This should include independent audit mechanisms, support for civil society collaboration, and the encouragement of media trainings on access to financial information. As a greater number of individuals and institutions develop expertise in security sector resource management, norms for high standards of financial integrity can be reinforced.

Integrated planning, policymaking, and budgeting systems can better deliver security to citizens, while enabling a more rational allocation of public resources to achieve national security priorities.

Notes

⇑ Rachel George, Mohamed Limam, Jessica Noll, Jessica Russell, Alam Saleh, Eitan Shamir, Robert Springborg, Christopher Swallow, “Government Defense Integrity Index,” Transparency International Defence and Security, 2020.

⇑ Nan Tian, “A cautionary tale of military expenditure transparency during the great lockdown,” WritePeace (Blog), Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, June 23, 2020.

⇑ “Security Sector Governance and Reform,” DCAF Backgrounder, Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces, May 2009.

⇑ Peter D. Feaver, “The Civil-Military Problematique: Huntington, Janowitz, and the Question of Civilian Control,” Armed Forces and Society 23, no. 2 (1996), 149-178.

⇑ Emile Ouédraogo, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa,” Africa Center Research Paper No. 6, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 2014.

⇑ Nicole Ball and Kayode Fayemi, eds., “Security Sector Governance in Africa: A Handbook,” Centre for Democracy and Development, 2004.

⇑ Judicial Review Cause No. 38 of 2020, High Court of Malawi, Lilongwe District Registry.

⇑ Zoltan Barany, “How to Build Democratic Armies,” PRISM 4, no. 1 (2012), 3-16.

⇑ Oluwakemi Okenyodo, “Governance, Accountability, and Security in Nigeria,” Africa Security Brief No. 31, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, June 2016.

⇑ Kwesi Aning and Joseph Siegle, “Assessing Attitudes of the Next Generation of African Security Sector Professionals,” Africa Center Research Paper No. 7, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, May 2019.

⇑ Bryan Vila and Cynthia Morris, eds., The Role of Police in American Society: A Documentary History (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999).

⇑ The State vs. The Inspector General of Police, The Clerk of the National Assembly, The Minister of Finance, Assessment of Compensation, Judicial Review Cause No. 7 of 2020, High Court of Malawi, Lilongwe District Registry (Civil Division).

⇑ “Peace and Corruption: Lowering Corruption – A Transformative Factor for Peace,” Institute for Economics and Peace, 2015.

⇑ Okenyodo, “Governance, Accountability, and Security in Nigeria.”

⇑ Maxime Ricard and Kouamé Félix Grodji, “Collaborative Policing and Negotiating Urban Order in Abidjan,” Africa Security Brief No. 40, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, November 2021.

⇑ National Consultative Council v. The State, MLR 243 of 1994, High Court of Malawi.

⇑ Ball and Fayemi, “Security Sector Governance in Africa,” 37.

⇑ Schedule 6, Section 24(1) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1993.

⇑ Anna Lührmann, Kyle L. Marquardt, and Valeriya Mechkova, “Constraining Governments: New Indices of Vertical, Horizontal, and Diagonal Accountability,” American Political Science Review 114, no. 3 (2020), 811-820.

⇑ Fairlie Chappuis, “Toolkit for Security Sector Reporting – Media, Journalism and Security Sector Reform,” Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance, July 2021.

⇑ Moussa Aksar, “Niger lost $120 million in arms deals over three years: government audit,” Reuters, May 27, 2020.

⇑ Jay Benson, Matthew Frank, Clayton Besaw, Jonathan Powell, Eric Keels, “Annual Risk of Coup Report—2019,” One Earth Future, April 2019.

⇑ Dan Kuwali, “Countering Coups: Strengthening Social Contracts in Africa,” Human Righter (blog), Raoul Wallenberg Institute, May 20, 2022.

⇑ Hans Born, Jean-Jacques Gacond, and Boubacar N’Diaye, eds., “Parliamentary Oversight of the Security Sector: ECOWAS Parliament-DCAF Guide for West African Parliamentarians,” Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces and Parliament of the Economic Community of West African States, 2011.