Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and intensified United States (US)–China competition have had two important geostrategic consequences. They have blown new life into the European Union (EU) and North Atlantic Treaty Organization, and accelerated expansion of the Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa (BRICS) bloc’s role and membership, as confirmed at this week’s Johannesburg summit.

These trends have hastened the shift away from a Western-led global order towards a new, still-to-be-crafted era of more uncertain and fluid multipolar connections, writes William Gumede, academic and Executive Chair of the Democracy Works Foundation. Change is in the air, and the next three decades will see the steady unfolding of this trend.

BRICS is cloaking itself in resentment against the West, particularly with the lingering effects of colonialism, imperialism and sanctions by leading Western countries. Another factor is the lack of global governance system reform, including the United Nations (UN) Security Council, World Trade Organization, and international finance institutions.

When considering BRICS’s future, it’s important to remember that India and China are systemic rivals. Competition between them will likely intensify, given nationalism, border disputes and competition in the South China Sea. And although countries’ motivations for wanting to join BRICS differ, few global south nations will exchange one hegemon (the US) with another (China).

How will the US and its Western allies’ react to a club that threatens their global dominance?

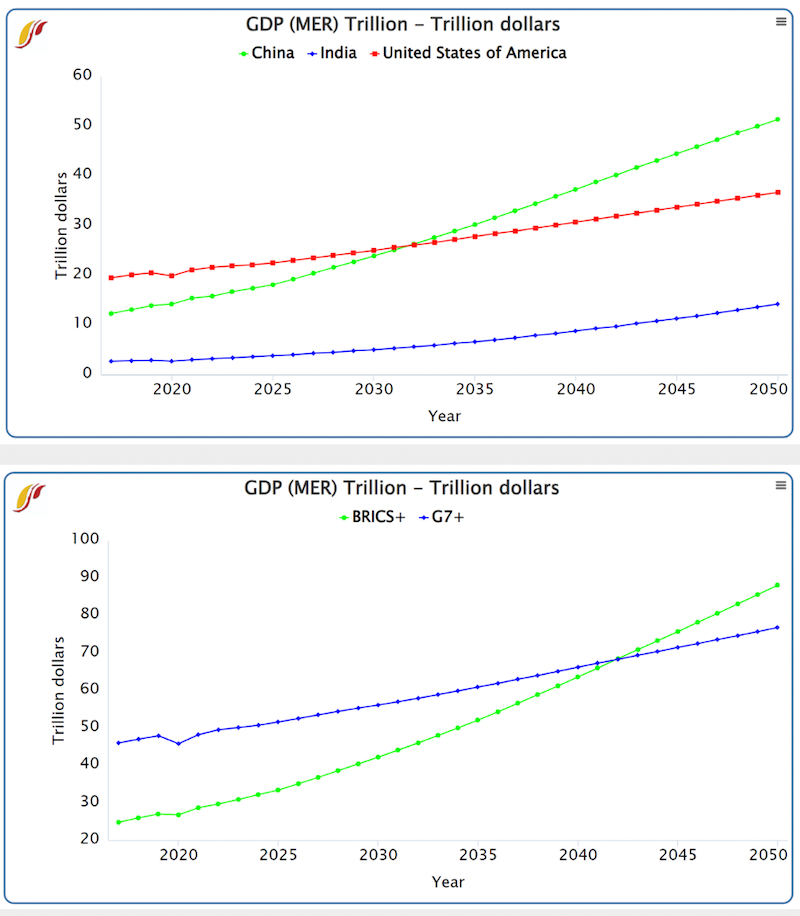

India is growing rapidly, but none of the African Futures and Innovation (AFI) forecasts indicate that its economy will compare with the size of China’s in the next half century, or see growth rates experienced by China and the Asian Tigers.

India experiences a more modest demographic dividend, although its population is now larger than China’s. Its services-led growth path produces slower productivity improvements than the manufacturing-driven transformation in China and the Asian Tigers. Whereas China’s economy is likely to overtake the US’ in size in about a decade, India’s could only do so towards the end of the century (Chart 1).

Chart 1: Forecast using International Futures model 8.04

Chart 2: Forecast using International Futures model 8.04; BRICS+ includes all likely members

BRICS country leaders decided at this week’s summit that Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) would join in January 2024. Egypt and the UAE are already members of BRICS’s New Development Bank. The inclusion of Argentina, not Uruguay, which is a member of the bank, was surprising. Inevitably bringing in Iran, which is under UN and other sanctions, will be the most controversial.

This first round of expansion is however only one side of the coin. How will the US and its Western allies’ react to a club that threatens their global dominance? Contrary to BRICS+ members, the West (North America, the EU and countries like Japan and South Korea) shares key values and is economically a much larger group than an expanded BRICS – and will be for decades. The election of someone like Donald Trump as US president in 2024 could, however be catastrophic for the West’s unity.

Average income in China is currently about 26% of that of the US. Only a collapse of the US economy would see income per capita parity between them. The situation regarding population size is of course different.

A forecast that compares the West’s economic size with a fully expanded BRICS+ shows that the much-talked-about de-dollarisation of the global economy will likely be slower than many think. BRICS+ will probably only surpass the West in about two decades.

BRICS members are generally united in their desire to move away from the dollar-backed international financial system. When the US Federal Reserve Bank hikes interest rates, the effect can plunge smaller economies into turmoil. It subjects them to exogenous shocks for no domestic reason, and the dollar provides the US with an extraordinarily powerful hammer to wield in its interests.

The most important shift in the dollar’s power will occur once oil and gas prices are no longer set in dollars

Russia, under Western sanctions, is most eager to end its punishment by the West, and has recently been joined by China, given the extent of China-bashing that passes for US foreign policy.

Rather than offering a single replacement for the US dollar, the diversification efforts will likely increase the power of BRICS members’ national currencies. All except Brazil have established alternatives to the dollar-denominated international payment messaging system, SWIFT, with varying degrees of success. Africa has the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS), an intercontinental platform to reduce reliance on dollar trading.

Already most BRICS bilateral trade payments are done in each country’s national currency, and the Johannesburg summit declaration proposes additional measures in this regard. Members are also diversifying their foreign reserves away from the US dollar, although mostly to the euro, Swiss franc, British pound or Japanese yen.

The most important shift in the power of the US dollar will occur once oil and gas prices are no longer set in US dollars. This was probably the main consideration for including Saudi Arabia and the UAE as new BRICS members.

Rather than a single currency, what will emerge are new currency blocs based on trade

There is no prospect of a replacement for the dollar in the foreseeable future. Trade among BRICS countries is too small to sustain a common currency. It only makes sense to trade in national currencies (not freely convertible) if the trade balance between the countries is more or less equal.

Russia, for example, recently sold lots of oil to India, dealing in rupees. But because India exports much less to Russia than it imports, Moscow now sits with rupees it cannot spend or convert – except to buy goods from India.

China’s renminbi isn’t sufficiently convertible and lacks the deep capital markets, market transparency, independent central banks and supporting financial institutions of Western banks. There are also perceptions of risk associated with China’s future – the country is an autocracy that will struggle to maintain stability as economic growth diminishes. India is also bound to oppose a common currency, given its concerns about China as a regional and potential global competitor.

So rather than a single alternative to the US dollar, what will emerge are new currency blocs (each bound to be quite leaky) based on bilateral and multilateral trade among the Middle East and China, South America, West Africa and elsewhere. And the slow reduction in the power of the greenback.