Key points

- The logic President Biden used for removing U.S. troops from Afghanistan applies to Syria. Since a U.S. intervention should be defined by clear, achievable goals, and since long-range strikes, instead of occupying forces, can accomplish U.S. counterterrorism goals, there is no good case for keeping U.S. troops in Syria either.

- Around 900 U.S. forces currently occupy territory in eastern and southern Syria, risking conflict with Syrian forces and local militias, as well as Russian, Iranian, and Turkish forces.

- ISIS’s territorial caliphate in Syria was eliminated in 2019. The few, small, remote areas the remnants of ISIS now hold are largely within territory held by Syrian government forces. Local forces can fight the remnants of ISIS.

- None of the other standard rationales for keeping U.S. forces in Syria—protecting the Kurds, countering Iran and Russia, unseating the Assad regime—justifies keeping troops in Syria either.

The logic of leaving Afghanistan also applies to Syria

In President Joe Biden’s remarks on August 31, 2021, about the withdrawal from Afghanistan, he outlined two key lessons the United States should learn from its nearly 20 years there. First, President Biden called for the United States to define its intervention by achievable goals, “not ones we’ll never reach.” He stated that “we succeeded in what we set out to do in Afghanistan over a decade ago. Then we stayed for another decade. It was time to end this war.” The original mission to disrupt Al-Qaeda after 9/11 and punish the Taliban for hosting the group was achieved by late 2002. Instead of withdrawing at that time, the U.S. mission aimlessly drifted for nearly two decades more. As President Biden put it, U.S. aims wandered into counterinsurgency, nation building, and “trying to create a democratic, cohesive, and united Afghanistan.”1 None of these aims were achieved or achievable.

Biden also correctly assessed that the U.S. interest in Afghanistan was limited to thwarting terrorists who possessed the capability and intent to strike the United States. Biden argued the United States “will maintain the fight against terrorism in Afghanistan” but U.S. forces “do not need to fight a ground war to do it.” This is because the United States possesses formidable over-the-horizon capabilities, including air, drone, and missile strikes, as well as raids, if necessary.2 While removing ground forces entails small sacrifices in intelligence gathering, exiting Afghanistan and relying on over-the-horizon strikes provides a cost-effective alternative to protect America’s security without undue risk to U.S. soldiers.3

Applied to Syria, this logic means, first, that the United States should avoid—or should have avoided—letting the mission drift from a clear counterterrorism fight against the Islamic State (ISIS) to open-ended purposes more removed from U.S. security and prosperity interests. In Syria, such open-ended purposes include defending Kurds, maintaining an insurgency against the Syrian government, and opposing Russian and Iranian influence there. Second, the United States should remove its forces from Syria since over-the-horizon capabilities are sufficient to achieve U.S. counterterrorism aims there.

The conditions and U.S. interests in Afghanistan are not identical in every aspect to those in Syria, of course. Notable differences include the presence of other foreign forces, a central government the United States does not underwrite, and possibilities for local populations to negotiate with the state for protection from terrorist groups. However, the reasoning used by the Biden administration regarding the American withdrawal from Afghanistan still applies. Like in Afghanistan, the United States can choose limited objectives over dangerously open-ended ones, and it can conduct any necessary counterterrorism missions without U.S. ground forces. The United States should therefore withdraw all remaining U.S. troops from Syria.

U.S. troops are no longer necessary to fight ISIS

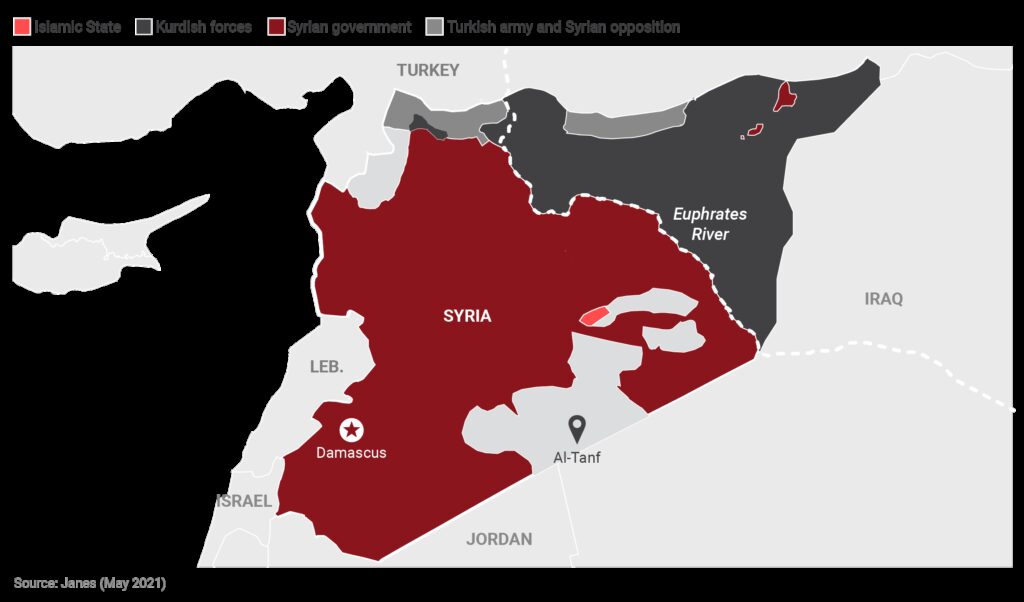

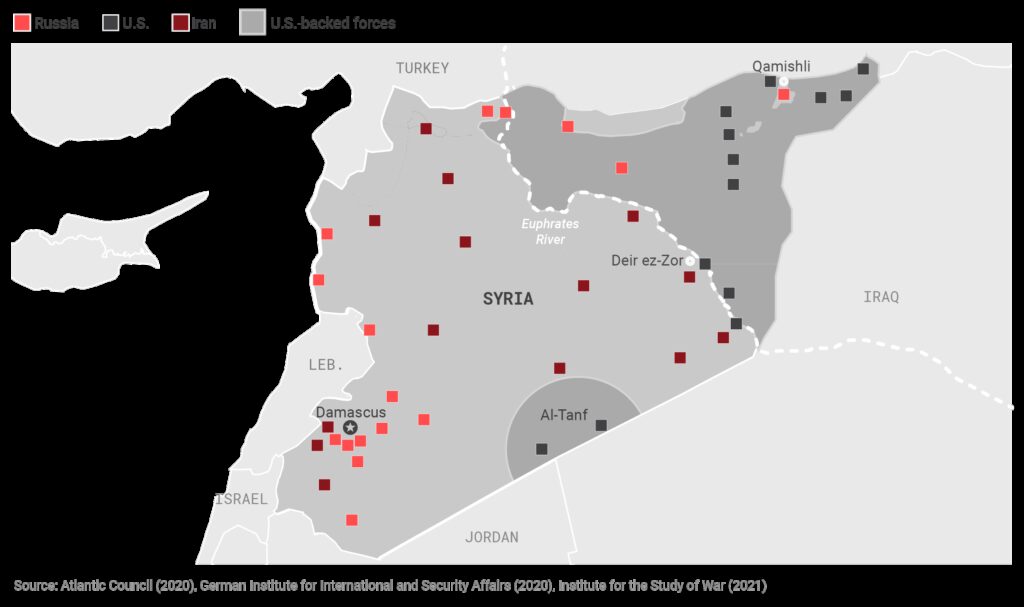

Around 900 U.S. forces currently operate in territory east of the Euphrates River in Syria and along Syria’s border with Jordan and Iraq in Al-Tanf. These deployments risk direct conflict with Syrian forces, as well as Russian, Iranian, and Turkish forces. The justification for their continued presence remains undefined.4

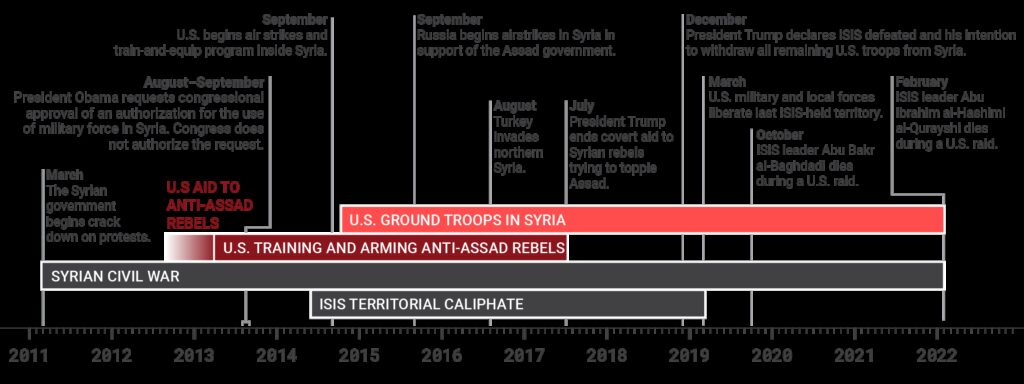

The U.S. ground forces presence in Syria, which started in 2015, was originally intended to eliminate ISIS’s territorial caliphate through “training, arming, and supporting forces” opposed to ISIS so they could “[reclaim] territory in Iraq and Syria.”5 In December 2018, with ISIS territory nearly gone and its fighters in displacement camps in the northeast, President Donald Trump declared victory over ISIS.6 This made sense, as ISIS was scattered and lacked the capability to hold significant territory. Critics of this view, including some Trump administration officials, argued that even though ISIS no longer held territory, there were still ISIS fighters in Syria capable of low-level, local attacks, and U.S. forces should remain to secure an “enduring defeat” of ISIS.7 But terror threats are nearly impossible to eradicate completely, especially in war-torn circumstances, like in Syria.

After the ISIS territorial caliphate was eliminated, the United States carried out a raid on October 27, 2019, that killed ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.8 Three years later, the United States conducted a similar mission on February 3, 2022, killing ISIS leader Abu Ibrahim Al-Hashimi al-Qurashi.9 Both leaders were in Idlib province in northwest Syria—not in areas near U.S. force deployments in the south and east. These raids demonstrate ISIS’s remnants are likely to persist in some form and these limited anti-U.S. threats can be targeted from afar without a permanent ground presence.

While not destroyed, ISIS today is depleted and weak, and the United States and the forces it backs in Syria only control part of the country. In fact, ISIS mostly operates in remote slivers of territory surrounded by Syrian government forces, not by U.S. forces. It remains the case that ISIS lacks the capability and resources to take and hold significant additional territory.10 That is as close to victory as one can reasonably expect given the persistent nature of terrorist groups such as ISIS. Defining victory more ambitiously makes it impossible to reach. Aiming for ISIS’s “enduring defeat” is synonymous with calling for a perpetual U.S. occupation of Syria. As President Barack Obama said in 2015, shortly after U.S. troops went into Syria, if the United States maintains a ground presence for too long and “[occupies] foreign lands, they can maintain insurgencies for years, killing thousands of our troops, draining our resources, and using our presence to draw new recruits.”11

Even now, years after ISIS’s territorial caliphate collapsed, U.S. officials unwisely continue in an open-ended mission in Syria. In early 2021, a State Department spokesperson reiterated that “the Biden administration is committed to carrying forward the important mission to defeat ISIS” and “ensure ISIS’s lasting defeat.”12 U.S. Army Col. Wayne Marotto, spokesperson for the Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve, echoed this point in August 2021, defining the U.S. mission as “in conjunction with our partner forces … to defeat Daesh and its remnants in designated areas of Syria … and set conditions for regional stability, security, and economic prosperity.”13

The idea that U.S. ground forces are needed permanently in Syria to combat ISIS remnants ignores the gains in U.S. surveillance and strike capability since Al-Qaeda’s heyday in the late 1990s in Afghanistan. Surveillance systems on unmanned aerial vehicles and satellites linked to strike capability—and the U.S. willingness to use this technology—have essentially made terrorist safe havens an anachronism.14 The United States can surveil and, if necessary, strike anywhere in Syria.

U.S. surveillance and strikes force groups such as ISIS to conduct riskier, more covert, and more decentralized methods of planning, recruiting, and training.15 A ground presence has some intelligence-gathering advantages, but occupational forces tend to generate resentment and resistance—likely energizing the terror threats the United States seeks to prevent and aiding recruitment for the very groups the U.S. forces target.16 In any case, the intelligence benefits of the U.S. presence in Syria are somewhat limited due to its geographic constraints and hostility toward the Syrian government. Relying on over-the-horizon capabilities is sufficient for the counterterrorism mission in Syria, just as it is in combatting terror threats in other places. It is also worth noting Israel’s impressive intelligence-gathering capabilities in Syria can aid in such targeting.

The U.S. does not have a vital national security interest in Syria

The United States has no compelling national security interest in Syria to justify an open-ended ground deployment of forces. In addition to the argument for an “enduring defeat,” three additional arguments for U.S. presence in Syria are (1) protecting U.S. partner forces in northeast Syria, (2) countering the influence of Iran and Russia, and (3) minimizing the human rights abuses of the Assad regime. The U.S. presence serves none of these objectives. The United States should acknowledge this reality on the ground and pull its forces out of Syria.

The Kurds should negotiate with the Syrian government

ISIS’s previously held territory in eastern Syria bordered and extended into Kurdish territory. This proximity pushed the Kurdish ground forces to the frontlines of the global counterterrorism effort.17 The United States entered the conflict in 2014 with airstrikes after ISIS forces took Kobani, a city in Syria’s north previously held by the Kurds. The United States has conducted joint operations with the Kurds, now organized into the Syrian Democratic Forces, ever since.18 In 2019, President Trump announced a partial withdrawal from Syria, specifically from the Syria-Turkey border, and received significant criticism domestically, with some accusing the United States of “abandoning the Kurds.”19

The United States does not owe its Kurdish partner forces a perpetual defense. U.S. interests aligned with Kurds’ interests in 2014 when U.S. airstrikes started, and in 2015 when U.S. ground troops arrived in Syria, because ISIS’s territory bordered Kurdish land then. This partnership was never meant to morph into the adoption of Kurdish democratic aspirations and certainly was not meant to guarantee the Kurds long-term security against their adversaries outside of ISIS.20

The U.S. presence and backing of Kurdish forces have also risked tension with NATO ally Turkey over the proximity of Kurdish territory and the prospective establishment of Turkey’s proposed border zone.21 The United States should not continue to allow its presence to put itself at odds with its allies, however problematic, without a strong interest in doing so.

The best course of action for Kurdish forces is not to remain dependent on U.S. support in perpetuity but to realign and negotiate with the Syrian government, which possesses an interest in providing them protection against both ISIS and Turkey. Through such negotiations, the Kurds could likely achieve what they had before the civil war, where they receive protection from Syrian state forces and keep their self-defense capabilities.22 Further, after a U.S. withdrawal, Syria, Russia, and Turkey could negotiate a buffer zone or de-escalation zone along the border to separate Kurdish forces from Turkey.

Russian and Iranian influence in Syria does not matter to the U.S.

Neither Russian nor Iranian influence in Syria is new, nor is it going away soon. Fewer than 1,000 U.S. troops could not realistically expel Russian or Iranian forces and, unlike the United States, Russia and Iran are in Syria at the request of the Syrian government. No matter the length of U.S. occupation, U.S. troops cannot erase the historical basis of these partnerships.

The roots of Syria’s relationship with Russia date back to the 1950s when Syria was a French protectorate and the Soviet Union supported its independence and legitimacy. The Soviet Union later supported Syria during the Six-Day War in 1967, a partnership which was solidified by the 1980 Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation and has persisted under the rules of both Hafez al-Assad and Bashar al-Assad.23

Similarly, Iran and Syria have been partners since Damascus stood by Tehran during the Iran–Iraq War, which began in 1980. They have long shared the common goal of countering Israel in the region, dating back at least as far as 1967, when Syria lost the Golan Heights, which it has since sought to take back from Israel.24 Such deeply entrenched partnerships are not likely to change if Bashar al-Assad remains in power, and pressure on his rule makes him more reliant on outside help. In short, the more the United States pressures the Syrian government, the more it will rely on Iran and Russia.

For the United States to stay to counter Russia or Iran is worse than fruitless; it is dangerous as well. Maintaining a U.S. force presence in Syria exposes American troops to clashes, such as in February 2018, when Russian private military contractors attacked Syrian Defense Forces in territory where U.S. troops were also stationed. The United States fired on those encroaching forces, resulting in as many as 300 Syrian and Russian casualties.25 As recently as October 2021, U.S. troops were at risk when Iran conducted a drone attack against U.S. sites in Al-Tanf.26 Military confrontation with Russia or Iran risks retaliation and escalation to a wider war. Thankfully, the clashes to date have resulted in only minor injuries for U.S forces.27 No possible benefit to U.S. interests justifies risking U.S. forces or escalation with Russia and Iran.

Even if Russia and Iran do maintain long-term influence in Syria, this will likely be a burden, not a bounty. The Syrian government will likely remain dependent on them to finance its reconstruction over the next decade or more. By 2017, Iran had reportedly spent more than $30 billion propping up the Assad regime.28 But that is a drop in the bucket of what Syria needs, given that the U.N. in 2019 estimated the cost of the reconstruction of Syria to be nearly $250 billion, roughly four times Syria’s prewar GDP.29 Given its own domestic troubles, Iran is striving to carry a burden it is unfit to shoulder.

Russia, likewise, has devoted extensive military and economic support to keep an economically weak ally with little international legitimacy, a burden for Russia exacerbated by U.S. and Western sanctions resulting from its illegal invasion of Ukraine. Since 2015, Russia has supported the regime through tens of thousands of airstrikes, the installation of S-300 and S-400 air defense systems, and the reinforcement of the naval base in Tartous and the air base near Khmeimim. Russia also deployed over 63,000 Russian troops by 2018 and hundreds of new Russian weapons, including SU-35 and SU-57 fighter jets and nuclear-capable TU-22M3 bombers.30 What this has bought Russia, beyond continued port access, is unclear.

All the while, Bashar al-Assad has proved resistant to serving Russian interests at the expense of his own self-interest. For example, Syrian forces have repeatedly broken Russia-brokered ceasefires, undermining the diplomatic legitimacy of Russia and the Astana talks.31 The Syrian government and Russia also diverge on territorial priorities: Syria maintains its “every inch” agenda, opposing any Russia-brokered deal to cede “buffer zones” to Turkey, whereas Russia prioritizes access to the bases along the Syrian coast.32 Also, Bashar al-Assad continues to appoint Alawite loyalists in command positions in an attempt to curb Russian influence over the Syrian intelligence forces.33

U.S. policy is prolonging, not helping, the Syrians’ humanitarian crisis

While the human rights abuses of the Assad regime are undeniable and condemnable, Bashar al-Assad is not stepping down nor is he likely to be removed. His support in Syria among the military and civilian Alawite population is secure.34 With Russia and Iran acting as his diplomatic and economic backers, the U.S. presence in Syria does little more than deny the Syrian government pockets of territory and a little bit of oil revenue—and delay the end of the war.

Beyond withholding territory, the purpose of the U.S. policy in Syria has been to (1) weaken the government, (2) pressure Bashar al-Assad into stepping down and setting up a provisional government, and (3) achieve concessions from the regime on human rights and aid for displaced persons within and outside of Syria. However, U.S. pressure has failed to change Bashar al-Assad’s behavior and has primarily affected Syrian citizens: prolonging the civil war, crippling the Syrian economy, and punishing any country willing to help Syria rebuild.35 While the United States intends to improve humanitarian conditions in Syria, the result has been the opposite.36 U.S. refusal to withdraw its forces and accept the Syrian government’s victory has caused severe shortages, contributed to the collapse of the Syrian pound, and frozen Syria’s status as a broken country, unable to recover from a costly and bloody war, with regional partners reluctant to aid in this recovery and risk economic retribution from the United States.

The United States can, after withdrawing its troops, negotiate with the Syrian government for the availability and delivery of humanitarian aid to Syrian citizens and promote the Astana and Geneva processes to move toward a conclusion to the civil war. Peace deals, either through the United Nations or regional efforts, could eventually provide the reassurance necessary for those displaced within Syria and abroad to return home safely. Achieving these objectives while the war continues is unlikely.

It is time for the U.S. to leave Syria

The Syrian civil war has persisted for more than 10 years. A continued U.S. presence in Syria does little more than prolong the conflict and freeze Syria in a broken stasis. U.S. forces just spent twenty years prolonging the conflict in Afghanistan, propping up the Afghan government when U.S. objectives had been achieved at least a decade earlier. The United States should cut short this same mistake in Syria.

Abandoning regime change and withdrawing U.S. forces from Syria acknowledges the reality that U.S. anti-ISIS and counterterror goals were long ago achieved, reduces risks to U.S. troops, decreases chances of costly escalation, and promotes humanitarian outcomes for Syrians who have already suffered years of civil war.