North Africa is a dynamic migration region that acts as the origin, transit and destination region for the various migratory flows that pass through it. These flows were traditionally dominated by sub-Saharan Africans who either remained in the region or transited through on their way to Europe. There has also been a movement of North Africans to Libya in search of employment, and in more limited cases, to board boats to Europe. From 2012 onwards, there has also been a movement of Syrian refugees to Libya, initially to wait for an end to the conflict at home and later to board boats to Europe. The individuals that travel along these routes form a complex group of people, including migrants, asylum seekers, refugees, minors, and involuntary migrants who possess differing motivations. Yet, they all follow the same journeys and are often in the hands of the same smugglers.For this reason, and for the purposes of this article, the word ‘migrant’ will be used broadly to refer to all people on the move through the region, unless a distinction is otherwise made.

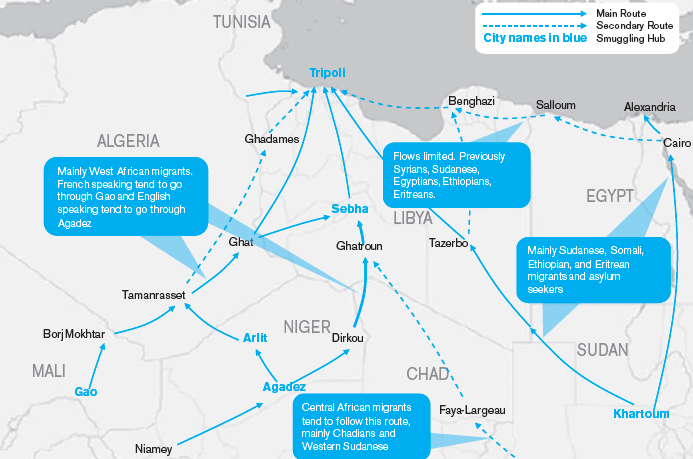

This article will provide an overview of the smuggling dynamics in the region by focusing particularly on movements along the Central Mediterranean route. Map 1 charts the Western, Central and Eastern Mediterranean routes and demonstrates how the flows have evolved between 2012-2015.

MAP 1 Central, Western and Eastern Mediterranean Routes 2012-2015

Main Routes

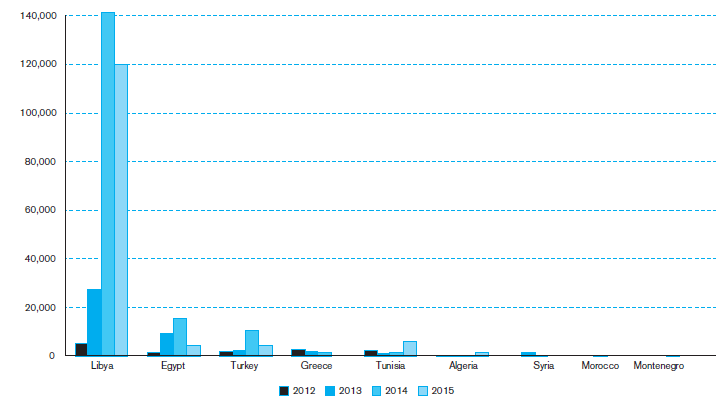

The Central Mediterranean route refers to the mixed migratory flow coming from Northern Africa to Italy and Malta. Map 2 charts all of the main smuggling routes through North Africa that fall along the Central Mediterranean route.

MAP 2 Main Smuggling Routes through North Africa along the Central Mediterranean route

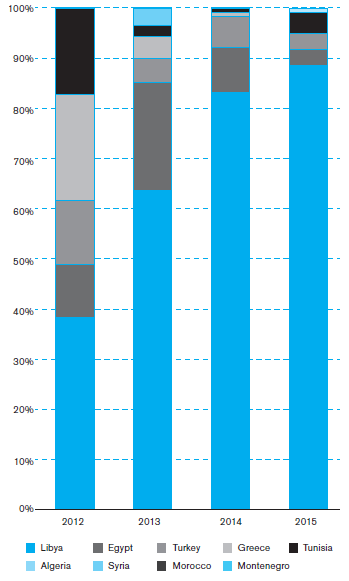

Libya has traditionally been a major transit point for sub-Saharan and West African migrants along this route and the main departure point for sea journeys across the Mediterranean. However, Egypt and Tunisia have also acted as departure points at particular points in time. Chart 1 details the number of irregular arrivals in Italy between 2012-2015, according to country of departure. It demonstrates that in 2014 there was an increase in departures from Egypt and in 2015, from Tunisia. Chart 2, however, demonstrates that the departures from the Libyan coast continued to account for a greater share of the total number of departures, with 84% of all arrivals in Italy in 2015 having departed from the Libyan coast (increasing from 62% in 2013).

CHART 1 Irregular Arrivals in Italy According to Country of Departure, in Absolute Terms

CHART 2 Irregular Arrivals in Italy According to Country of Departure, as a Proportion of the Total

Libya is the most attractive North African country along the Central Mediterranean route because in addition to being a departure point for Europe, it also offers a great deal of employment opportunities. Moreover, there is very little control of its borders following the 2011 Libyan Revolution and particularly after the 2014 political crisis. When migrants and asylum seekers in Egypt tried to resume direct sea crossings to Italy in 2013 and 2014 (mainly in response to increasing instability and risks in Libya after the 2014 crisis), the Egyptian government stepped up its arrests of anyone attempting to depart irregularly and curtailed the trend. While the instability in Libya today and the consequent dangers for migrants have presumably made the country less desirable than before, the inflows remain strong, thereby confirming that the migratory routes into the country and the transit routes through the country are now well established. In 2016, the number of departures from the Egyptian coast for journeys to Italy has increased.

The Dynamics of Smuggling

As can be seen in Map 2, migrants typically make their journey in stages. This leads to a variety of smugglers being used for the different stages, and they can be found in a variety of locations (smuggling hubs are marked in blue on Map 2).

Research conducted in Libya in 2013 revealed that there are generally two types of smugglers along the migratory routes through the Central Mediterranean: smugglers that facilitate the journey itself (referred to as the muhareb in Arabic) and smugglers who act as intermediaries and create the market for migrants (referred to as the samsar in Arabic). Usually, the samsar will take the migrants to a holding location, and once there are enough of them, a muhareb will be invited to come and offer his services to the migrants. The migrants will pay the muhareb for the journey and the muhareb will give a proportion of the payment to the samsar.

Key Locations

Traditionally, the crossing of the Sahara, in order to move from sub-Saharan Africa to North Africa, has always been facilitated by a smuggler as the harsh terrain necessitates the help of someone who is accustomed to it. This is particularly evident for journeys from Agadez to Sabha, from Dongola (Sudan) to Kufra or Sabha, and across the Algerian desert and into Libya (Tamanrasset to Djanet or Debdeb).

Moreover, moving through Libya, once one has entered through one of its southern borders, is also very difficult and requires a smuggler, given that the ongoing political crisis of 2014 has led to conflict in certain parts of the country, as well as the presence of checkpoints across the country, controlled by both the State and non-state actors.

Key Actors

Members of certain Saharan tribes are known to be active in the smuggling business because of their extensive knowledge of the desert and familiarity with crossing it. The historic marginalization of such tribes under Gadhafi’s regime also encouraged entry into the smuggling business for the sake of a livelihood (Reitano, 2014).

Members of the Tuareg tribe tend to dominate routes through North Niger and Algeria and into Ghat and Ghadames in Libya. Members of the Tebu tribe are thought to be active on routes through the Tibesti Mountains and on some routes through the western part of Kufra. (Police officers and border post officials in this area are often Tebu, which likely helps facilitate passage for smugglers.) Members of the Zway tribe are believed to be controlling most of the smuggling routes to the eastern part of Kufra from Sudan and Chad. There has also been some competition between the Zway and the Tebu to control the smuggling routes in and out of Kufra, particularly because the local economy has been so dependent on this business.

There are suggestions that the conflict in Libya that began in 2014 has led to more groups entering the smuggling trade as a way to fund their activities and, as such, migrant smuggling in Libya has also become an indicator for the development of the conflict in general. For example, migrants who were detained in Libya, report that detention centre guards sometimes offered to facilitate their release from detention if they purchased a boat journey to Europe from a smuggler. Others also intimated that they were sometimes put on a boat, when in detention, without having paid the smuggling fee. Moreover, in April 2014, only around 20% of detention centres in Libya were reported to be official detention centres by the Ministry of Interior (IOM, 2015). Such stories suggest that there may be state actors involved in smuggling in Libya and that non-state actors potentially establish migrant detention centres as a way to generate the market for smuggling services.

The Economics of Smuggling

Prior to 2014, journeys to North Africa and from North Africa to Europe could be categorized according to standard prices. In 2014, however, the price of a journey facilitated by a smuggler was dependent upon the nationality of the migrant (Syrian refugees paid higher prices than sub-Saharan African migrants and asylum seekers), the smuggling ring the migrant came into contact with in Libya, and the level of service that the migrant was willing to pay for (at a higher price, a migrant could secure a place on the top deck of the vessel and receive a life jacket). While in 2013, the most expensive journeys were in the vicinity of USD $6,000, in 2014, they could be up to USD $20,000. The potential for increased revenue came when a greater number of Syrians entered the market, as they tend to have greater economic means compared with sub-Saharan Africans, and by the general increase in traffic along North African routes in 2014. The GITNOC (2015) estimates the migrant trade off the coast of Libya at US $255 – 323 million per year in Libya alone.

Libya is the most attractive North African country along the Central Mediterranean route because in addition to being a departure point for Europe, it also offers a great deal of employment opportunitiesAs most migrants do not have enough money for the entire journey from the outset, many work in transit countries along the way. In some cases, a smuggler might allow a migrant to continue the journey, even if they do not have the requisite funds, on the promise that they will pay off their debt to the smuggler at the destination. Such practices often lead to situations of bonded labour and this thereby demonstrates the fine line that exists between smuggling and trafficking. It is also common for smugglers to direct female migrants who are traveling from West Africa to North Africa, and who are out of money, to Arlit (Niger) to work in prostitution rings, which are quite common there, as a way to generate income for the next phase of their journey, which often makes them vulnerable to trafficking.

Also, while migrant smuggling in North Africa has traditionally been linked with trafficking in other commodities, such as weapons, drugs, and subsidized goods, USIP (2014) identifies an increase in the intermingling of migrant smuggling and drug trafficking in recent years.