After Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the jihadi faction that runs the northwestern province of Idlib, moved into Afrin, Turkey stands to gain.

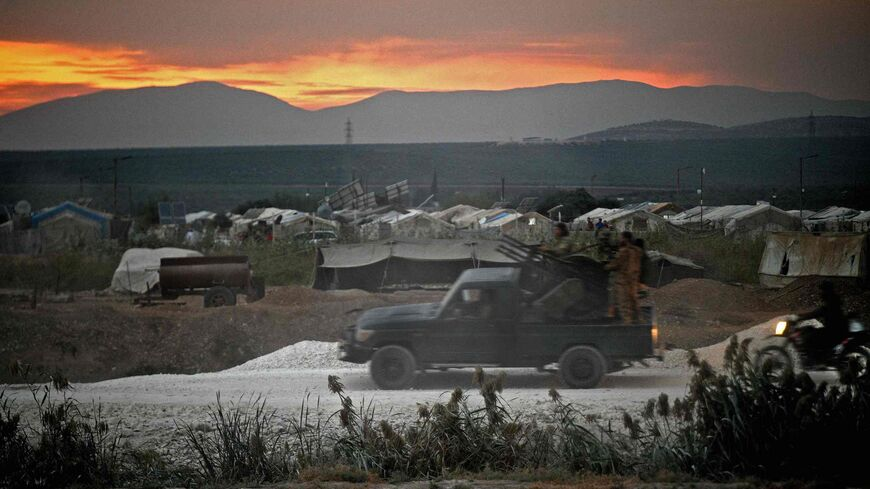

With the world’s attention focused on Ukraine, a potentially transformative development in northern Syria went largely unnoticed. On Oct. 13, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the jihadi faction that runs the northwestern province of Idlib and is by far the most powerful of all the Sunni rebel groups in Syria, moved into Afrin, the Kurdish-majority enclave that was occupied by Turkey in 2018. It did so at the expense of rebel factions operating under the umbrella of the Syrian National Army (SNA) and with the help of other factions also allied with the SNA. The latter include the Sultan Suleyman Shah Division, the Hamza Division and Ahrar al-Sham, which all have close ties to Ankara.

The question of where Turkey stands in this power grab is of critical importance in terms of the balance of power in northern Syria. HTS is designated as a terror group by Turkey as well as by the United States. However, it’s an open secret that Turkey and HTS collaborate on the ground with the latter facilitating the deployment of Turkish forces in Idlib, which began under the now largely lapsed Astana agreement.

Did Ankara silently assent or was it unable to prevent the HTS from muscling in?

Various outlets have suggested that Turkey intervened to de-escalate the clashes that were triggered by the Oct. 7 assassination of an opposition activist and his pregnant wife. HTS appears to have seized on the quarrel to make its move.

By Saturday, HTS had reportedly withdrawn some of its forces from Afrin. Ankara is also said to have persuaded HTS to not move into Azaz, a critical logistical hub bordering Turkey, on which the jihadis had set their sights. But today there were reports of renewed clashes with the HTS seeking to advance on Azaz yet again.

Turkey has thousands of troops in northern Syria and is a vital lifeline for aid and commercial goods flowing into the region, notably Idlib. It is unlikely that HTS could have acted without at least an amber light from Ankara, many say.

Charles Lister, a senior fellow at the Middle East Institute who closely monitors northwest Syria, noted that when the HTS made forays into Afrin in the past, “again opportunistically taking advantage of intra-SNA tensions,” a phone call from Turkey’s national spy agency, MIT, saw the group return to Idlib. “On this occasion, no such Turkish order appears to have come,” Lister noted in a recent essay. And HTS’ advance on Afrin proceeded “virtually unchallenged.”

What has changed? Well-placed sources with close knowledge of Ankara’s thinking assert that Turkey has multiple motives for wanting to let HTS and its savvy leader, Abu Mohammed al-Golani, consolidate their grip.

For one, HTS is the sole force that comes close to being any kind of a match for the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the US-backed, Kurdish-led group that together with its civilian arms is running northeastern Syria. Turkey has launched multiple assaults against the group on the grounds that they pose a threat to its national security. Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has made clear his intentions to establish a 30-kilometer-deep security belt inside Syria that is meant to hold the SDF at bay. The SDF’s repeated calls for peaceful relations have fallen on deaf ears.

“Turkey is definitely behind HTS,” said Salih Muslim, co-chair of the Democratic Unity Party that shares power in the Kurdish-led administration in northeast Syria. Muslim said he had information that MIT had been holding meetings with Golani over the past four months to discuss bringing opposition factions under HTS control and “annihilating” those who refused to yield. “There are many tough fighters within the HTS, be they from al-Qaeda, the Islamic State (IS) and the like, and we believe they are preparing them for battle and plan to get rid of the undisciplined ones so as to create a more effective force to fight against us,” Muslim told Al-Monitor. Turkey’s plan, he added, was to deploy HTS in the Euphrates Shield zone with a view to seizing the SDF-controlled town of Manbij, in line with Erdogan’s long-running threats to attack northeast Syria again.

If true, this would mark a U-turn. Until recently, as per its Astana mandate agreed upon with Russia and Iran, Turkey’s job was to recruit “moderates” from HTS’ and other extremist groups’ ranks and incorporate them into the SNA. Over time, this was supposed to weaken and marginalize the jihadis.

But if it is, the other motive is to bring stability in the areas it occupies together with the SNA. Afrin in particular has been convulsed with lawlessness, corruption and a panoply of rights abuses ranging from extortion to rape.

Idlib, by contrast, where the National Salvation Government formed by Golani runs the show, has provided relative stability, albeit with an iron fist that squeezes women more than any.

One of the sources speaking not for attribution to Al-Monitor said the Turkish government wants to “establish an SDF-type model in its own zone.” (It’s a peculiar aspiration. The Kurds with their pursuit of gender equality and unequivocally secular mores are the polar opposite of the HTS.)

Stability in the Turkish-controlled zones would make it easier, at least in theory, for Turkey to resettle the millions of Syrian refugees whom Erdogan has pledged to repatriate under “humane conditions.” Anti-refugee sentiment is growing by the day amid skyrocketing inflation, and Erdogan and his ruling Justice and Development Party face re-election next year. He needs to show something for his pledge before then.

“Due to HTS’ designation as a terrorist organization, the group is a source of deep concern within the broader state apparatus, but MIT, in particular, has driven a policy that acknowledges a simple and very difficult truth: that HTS has been instrumental in keeping Idlib stable for two years,” Lister told Al-Monitor. While Lister believes that Turkey is “resigned to a likely inevitable outcome: HTS expanding its unilateral rule,” the Turkish-based sources insisted that Turkey was helping to drive it.

A stronger HTS would serve as greater leverage in future talks with Syria compared with the array of weak, ineffectual and perennially squabbling warlords under its wing. And should Syrian President Bashar al-Assad contemplate a deal with the Kurds similar to that struck by his late father, Hafez, against Turkey, Ankara can brandish the HTS stick in response.

However, Erdogan has aired his willingness to talk to his one-time nemesis in the biggest U-turn over Syria in recent years. And Golani, according to the same sources, is interested in being part of the conversation, never mind that Turkey could ditch him if Assad agrees to clobber the Kurds.

In truth, it’s hard to imagine any circumstance under which Assad would engage with jihadis. He’s already declared that he won’t sit down with the Turks until they withdraw from his country. Assad and his Russian allies are bent on retaking Idlib by force.

But the Kremlin’s disastrous intervention in Ukraine may yet impact Syria in unpredictable ways. For now, the most immediate effect has been an expansion of Iran’s influence, which could in turn force a rethink of Western thinking on HTS, or so Golani hopes.

Golani’s pragmatism has been in evidence for some time. He has been determinedly seeking to distance himself from his al-Qaeda roots, a makeover that has seen him don a Western-style suit, court Christians in Idlib, and batter smaller al-Qaeda and IS-linked rivals. Ankara appears to be playing along, allowing a PBS reporter among others to cross the Turkish border to interview him.

However, it didn’t take long for the mask to slip. When the Taliban took over Afghanistan in August 2021, HTS hailed the occasion as a major victory for global jihad. “The Islamic State established a so-called caliphate; now HTS is busy establishing an Islamic emirate,” said Muslim, the Syrian Kurdish leader.

The Biden administration is clearly unswayed by Golani’s gyrations and shows no inclination for delisting HTS. But then neither does Turkey. This is probably because the designation gives it leverage over the group while shielding it from further opprobrium over its lax attitude toward extremists.

Either way, any further gains for HTS spell “an absolute catastrophe” for Syria’s opposition, Lister contended. “And for that reason alone, this has the potential to impact the trajectory of the entire Syria crisis. The stakes involved here are enormous, and to put it bluntly, the conclusion will most likely be defined by Turkey’s decisions,” he said.

Ankara has yet to formally comment.