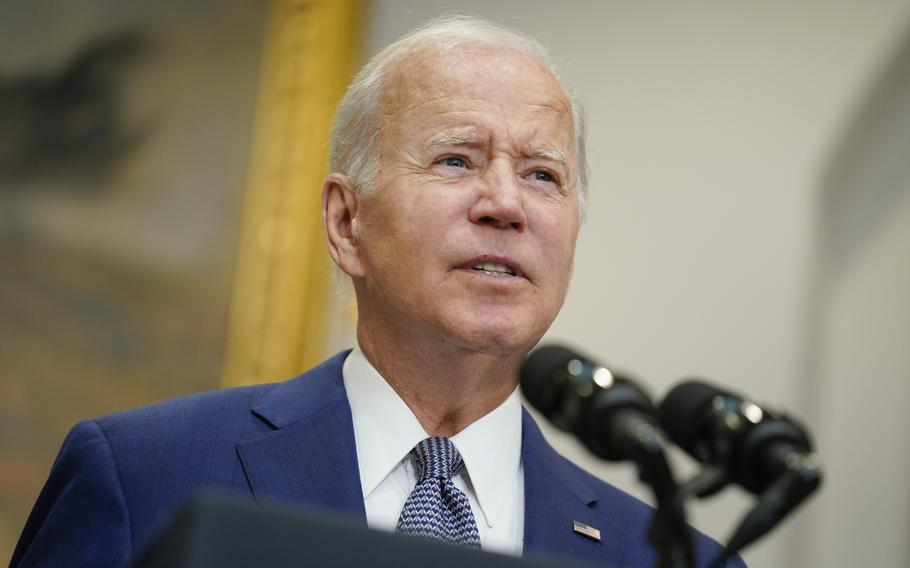

Joe Biden took office looking to reshape U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East, putting a premium on promoting democracy and human rights. In reality, he has struggled on several fronts to meaningfully separate his approach from former President Donald Trump’s.

Biden’s visit to the region this week includes a meeting with Saudi Arabia’s King Salman and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the oil-rich kingdom’s de facto leader who U.S. intelligence officials determined approved the 2018 killing of U.S.-based journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Turkey.

Biden had pledged as a candidate to recalibrate the U.S. relationship with Saudi Arabia, which he described as a “pariah” nation after Trump’s more accommodating stand, overlooking the kingdom’s human rights record and stepping up military sales to Riyadh.

But Biden now seems to be making the calculation that there’s more to be gained from courting the country than isolating it.

Biden’s first stop on his visit to the Mideast will be Israel. Here, again, his stance has softened since the firm declarations he made when running for president.

As a candidate, Biden condemned Trump administration policy on Israeli settlements in the West Bank. As president, he’s been unable to pressure the Israelis to halt the building of Jewish settlements and has offered no new initiatives to restart long-stalled peace talks between Israel and the Palestinians.

Biden also has let stand Trump’s 2019 decision recognizing Israel’s sovereignty over the Golan Heights, which reversed more than a half-century of U.S. policy.

The Biden administration “has had this rather confusing policy of continuity on many issues from Trump — the path of least resistance on many different issues, including Jerusalem, the Golan, Western Sahara, and most other affairs,” says Natan Sachs, director of the Center for Middle East Policy at the Brookings Institution.

Now Biden appears to be trying to find greater equilibrium in his Mideast policy, putting focus on what’s possible in a complicated part of the world at a time when Israel and some Arab nations are showing greater willingness to work together to isolate Iran — their common enemy — and to consider economic cooperation.

“Biden is coming in, in essence making a choice,” Sachs said. “And the choice is to embrace the emerging regional architecture.”

Biden on Saturday used an op-ed in the Washington Post — the same pages where Khashoggi penned much of his criticism of Saudi rule before his death — to declare that the Middle East has become more “stable and secure” in his nearly 18 months in office and he pushed back against the notion that his visit to Saudi Arabia amounted to backsliding.

“In Saudi Arabia, we reversed the blank-check policy we inherited,” Biden wrote. He also acknowledged “there are many who disagree” with his decision to visit the kingdom.

He pointed to his administration’s efforts to push a Saudi-led coalition and Houthis to agree to a U.N.-brokered cease-fire — now in its fourth month — after seven years of a war that has left 150,000 people dead in Yemen. Biden also cited as achievements his administration’s role in helping arrange a truce in last year’s 11-day Israel-Gaza war, the diminished capacity of the Islamic State terrorist group in the region and ending the U.S. combat mission in Iraq.

But Biden’s overall Mideast record is far more complicated. He has largely steered away from confronting some of the region’s most vexing problems, including some that he faulted Trump for exacerbating.

Biden often talks about the importance of relationships in foreign policy. His decision to visit the Mideast for a trip that promises little in the way of tangible accomplishments suggests he’ i trying to invest in the region for the longer term.

In public, he has talked of insights gained from long hours over the years spent with China’s Xi Jinping and sizing up Russia’s Vladimir Putin. He’s relished building bonds with a younger generation of world leaders including Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Japan’s Fumio Kishida

Biden has met every Israeli prime minister dating back to Golda Meir, has a long-standing relationship with Jordan’s King Abdullah II and was deeply involved as vice president in helping President Barack Obama wind down the Iraq War. But Biden, who came of age on the foreign policy scene during the Cold War and sees the rise of China as the most pressing crisis facing the West, has been less oriented toward the Middle East than Europe and Asia.

“He doesn’t have the personal relationships. He doesn’t have the duration of relationships,” said Jon Alterman, director of the Middle East Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

He arrives at an uncertain moment for Israeli leadership. Former Prime Minister Naftali Bennett and Yair Lapid last month dissolved the Knesset as their politically diverse coalition crumbled. Lapid, the former foreign minister, is now the caretaker prime minister.

Biden also will face fresh questions about his commitment to human rights following the fatal shooting of Palestinian American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh. Independent investigations determined that she was likely shot by an Israeli soldier while reporting from the West Bank in May.

The Abu Akleh family, in a scathing letter to Biden, accused his administration of excusing the Israelis for the journalist’s death. The State Department last week said U.S. security officials determined that Israeli gunfire likely killed her but “found no reason to believe that this was intentional.”

Two of the most closely watched moments during Biden’s four-day Middle East visit will come when he meets with Israeli opposition leader and former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and when he sees the Saudi crown prince.

But neither encounter is likely to dramatically alter U.S.-Mideast political dynamics.

Both leaders seem to have set their eyes on a post-Biden America as the Democratic president struggles with lagging poll numbers at home driven by skyrocketing inflation and unease with Biden’s handling of the economy, analysts say.

“Both of these leaders in my judgment are now looking past the Biden administration, and looking very much forward to the return of Donald Trump or his avatar,” said Aaron David Miller, who served six secretaries of state as an adviser on Arab-Israeli negotiations and now is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “I think it’s a complex trip, and I think we should be extremely realistic about these expectations.”

Biden’s prospects for progress on returning the U.S. to the Iran nuclear deal, brokered by Obama in 2015 and withdrawn from by Trump in 2018, remain elusive. The administration has participated indirectly in Vienna talks aimed at bringing both Washington and Tehran back into compliance with the deal. But the talks have thus far proved fruitless.

As a candidate, Biden promised the Saudis would “pay the price” for their human rights record. The sharp rhetoric helped Biden contrast himself with Trump, whose first official foreign trip as president was to the kingdom and who praised the Saudis as a “great ally” even after the Khashoggi killing.

Biden’s tough warning to the Saudis came at a moment when oil was trading at about $41 barrel; now, prices are closer to $105. The elevated oil prices are hurting Americans at the gas pump and driving up prices on essential goods, while helping the Saudis’ bottom line.

White House officials have said energy talks would make up one component of the Saudi leg of the president’s visit, but they have played down the prospect of the Saudis agreeing to further increase oil production because the kingdom says it is nearly at production capacity.

But Bruce Riedel, who served as a senior adviser on the National Security Council for four presidents, said the Saudi Arabia visit is “completely unnecessary” under the circumstances.

“There’s nothing that Joe Biden is going to do in Jeddah that the secretary of state or the secretary of defense, or frankly, a really good ambassador couldn’t do on his own.,” Riedel said. “There’s no outcome that’s going to come from this that really warrants a presidential visit.”