With all due respect to the commentary about Saudi oil production, there may be other reasons behind Biden’s Middle East trip next week, at a time when he has so many problems at home

Ostensibly, U.S. President Joe Biden’s trip to Saudi Arabia and Israel next week doesn’t make sense. The cost-benefit calculus is questionable as the tangible costs are clear and significantly outweigh any possible benefits. Unless it’s about something other than just visiting Israel and Saudi Arabia.

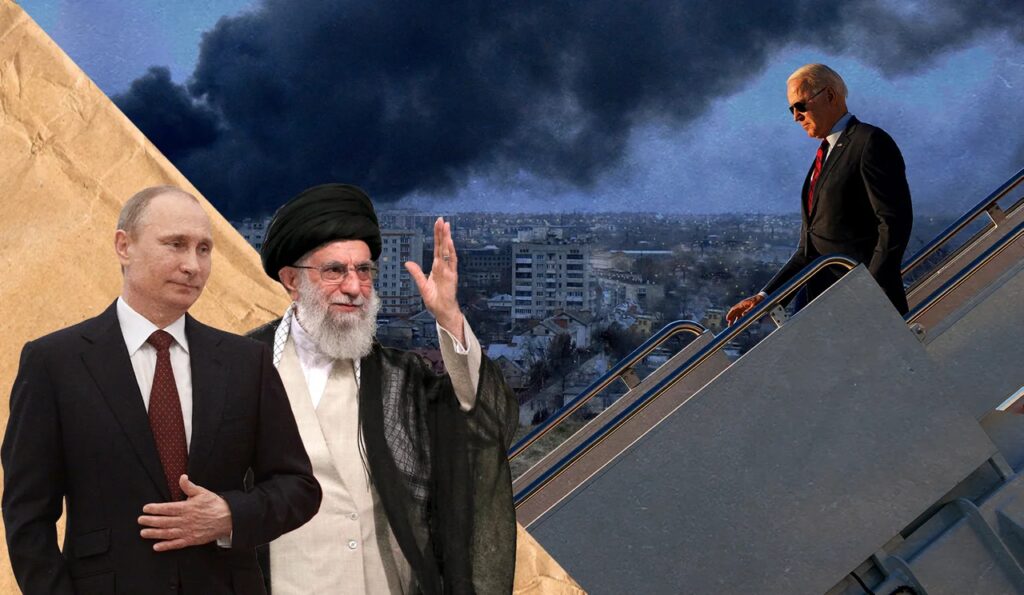

That “something” could be two scenarios. First, the United States anticipates Russian escalation in Ukraine, with a possibly expanded role for NATO as a result. This would entail more sophisticated weapons being transferred to Ukraine, NATO naval escorts for vessels carrying grain from the port of Odesa in the Black Sea, and Russia escalating attacks in response. In terms of oil markets and regional alliances, the Americans want to reassert their presence, offer assurances and elicit cooperation ahead of such a contingency.

Second, the U.S.’ working assumption for the foreseeable future is that a new nuclear deal will not be signed with Iran, and consequently Tehran may accelerate its “threshold state” progress and accumulate a weapons-grade amount of enriched uranium. Simultaneously, Iran may expand its missile and drone programs, and launch further destabilizing regional activities and use violent proxies in Yemen, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, the Palestinian territories and targets away from the region.

With Israeli, Saudi and Emirati anxieties regarding Iran’s intentions and the U.S. Fifth Fleet – part of the Central Command (CENTCOM) – headquartered in Bahrain, it seems only natural that the administration would want to bolster a regional alliance, but with U.S. involvement.

But the initial reasons given for the visit just don’t add up.

The trip cannot be about increased Saudi oil production, because the kingdom can’t achieve that. This is not about the United States reasserting commitments and involvement in the region, because there is an inexorable and geopolitically logical disengagement trajectory, with foreign policy priorities shifting to the Indo-Pacific.

It surely isn’t about reigniting an Israeli-Palestinian “peace process.” The Americans are too disillusioned and disinterested to undertake that ungrateful task.

It cannot be merely about U.S. support for a regional counter-Iran coalition. That could have been handled by Secretary of State Antony Blinken. The president has been adamantly averse to the idea of meeting Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman because of his involvement in the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018, with Biden vowing to turn Saudi Arabia into a “pariah” state. In addition, the president just returned from a trip to G-7 and NATO summits. Surely there must be a compelling argument, or major foreign and defense policy priority, that would justify such a crude reversal of policy.

Furthermore, the president – who ran for office because “there’s a fight for the soul of America” and was elected to fix the republic – is facing severe criticism from Democrats at home for inadequately responding to internal political strife and his timid, almost indifferent, response to a series of divisive and dramatic Supreme Court decisions that profoundly affect his electoral base.

It is improbable that this cost-benefit equation escaped the White House political and communications people or the foreign policy ecosystem around the president.

So why is he coming to the Middle East? It has to be for other, potentially bigger, things: Russia and Iran.

Biden believes he is in an equidistant position between two dangerous and ominous trends engulfing the United States and the West: Trumpism at home, Putinism abroad. Both represent historical challenges and clear and present dangers to the American order Biden has passionately believed in since his formative years in politics in the 1970s.

Vladimir Putin challenges the rules-based, U.S.-dominated world order of post-1945 and again after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. To that end, he invaded Ukraine.

Donald Trump represents an assault on the basic tenets of American democracy and the political system. To that end, his acolytes invaded Capitol Hill last year.

From Biden’s perspective, “Putinism” and “Trumpism” are not dissimilar phenomena in either style or substance. In fact, they complement each other in terms of the response they demand from the United States. The same formative experiences, political maturation and set of values that make Biden the ideal president to counter Putinism – the epicenter of anti-American, anti-Western autocratic and belligerent sentiments and actions – arguably make him less suitable to deal with Trumpism, with a GOP that follows no rules and an era of disdain for facts, a transactional relationship with the truth, and incendiary, toxic politics.

In other words, Biden, a creature of the Cold War era, is robustly equipped to deal with Putinism, but perhaps not with Trumpism and America’s unraveling at the seams. So, he may be beginning to define and frame his legacy in foreign policy – and that brings us back to his Middle East trip.

From the outset of the Ukraine crisis, one of the most reasonable and attractive sounding (yet flagrantly misused) arguments about the trip was that it was intended to get Saudi Arabia to increase oil production to compensate – particularly – Western Europe for the shortage caused by a major reduction in Russian oil flow.

Immediately after the Russian invasion in February, the idea that the United States needed to dramatically mend ties with the Saudis in return for more oil gained traction, and was frequently used by politicians and the media as a winning eureka argument. It was so simple and appealing that some did instant math and argued that if Biden were to just shake hands with Crown Prince Mohammed, gasoline prices at the pump would come down immediately and inflation would instantly be curbed.

It was a fundamentally flawed and dilettante argument. Why? Because Saudi Arabia doesn’t really have the capacity to increase production in quantities sufficient to offset any Russia-generated oil shortage. The relevant term here is “spare capacity.” The U.S. Energy Information Administration defines simply and clearly what this constitutes: production that can be brought online [i.e., into world oil markets] within 30 days and sustained for at least 90 days.

But the argument’s weakness lies also in the Saudi-provided numbers on actual oil reserves and production capabilities. In short, the numbers don’t add up. Basically, over the past 32 years, Saudi Arabia “has physically pumped and removed forever from its oil fields a total of 95,682,560,000 barrels of crude oil. Over the same period, there has been no significant discovery of major new oil fields. Despite this, Saudi Arabia’s crude oil reserves have not gone down, but rather have actually gone up,” writes Simon Jenkins on the Oilprice website.

In the best case scenario, Saudi Arabia can hypothetically increase production by 550,000 to 600,000 barrels per day, above the 10.3-10.5 million barrels it currently produces daily (May figures). But even that figure seems overly optimistic. Two weeks ago, French President Emmanuel Macron divulged that in a phone call with UAE Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed, “He told me two things: ‘I’m at a maximum, maximum (production capacity).’ … And then he said [the] Saudis can increase by 150 [thousand barrels per day]. Maybe a little bit more, but they don’t have huge capacities before six months’ time.”

So there you have it. Biden’s trip is not about oil production.

When that became clear, the U.S. administration hinted that the visit was in fact essentially about an ad hoc Israeli-Gulf defensive alliance to counter Iran. There were references to opaque U.S. auspices, and general commitments of assisting with anti-aircraft and anti-drone defenses and technology.

With an eye on Pacific allies, Biden will make it clear the United States is not abandoning allies or swiftly disengaging from the Middle East. The Americans demonstrated this with NATO, so why not recommit to a Mideast alliance?

Biden sees U.S. foreign policy as being about forging, strengthening and managing alliances. The president is therefore going to Israel, then to the Gulf Cooperation Council summit in Jeddah at the invitation of King Salman. This summit will include Egypt, Jordan and Iraq.

That makes much more sense, certainly if a statement on an improvement in Israeli-Saudi relations is made. But it still raises the question of whether all this justifies a presidential visit and expending political capital when America is in internal turmoil.

It does, to a limited degree, if the contours of such cooperation or a quasi-alliance have been drafted, agreed and finalized already, and Biden is there for the declaration.

Only if Biden’s trip is really about Russia and Iran does it makes foreign policy sense. Otherwise, it could turn out a complete waste of time – something Biden cannot afford right now.