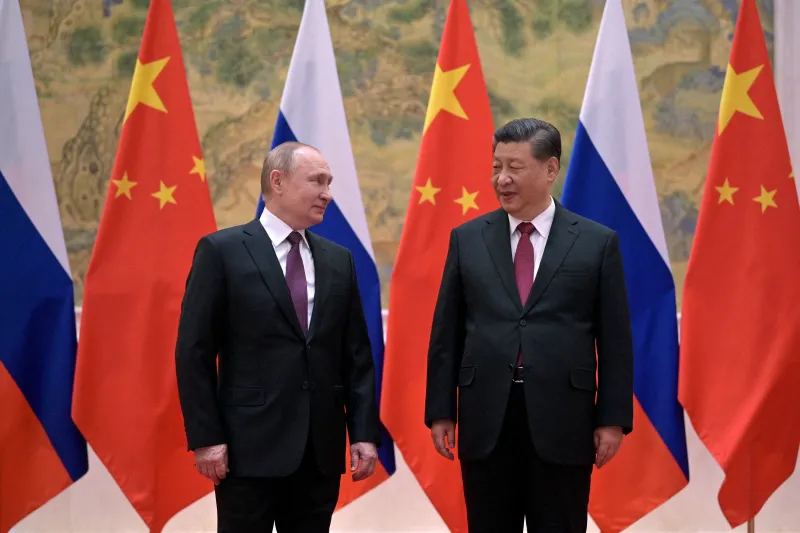

Regardless of whether Beijing had advance warning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s decision to issue a statement last month outlining a “no limits” partnership with Moscow was arguably the single biggest foreign policy blunder of his nearly ten years in power. Russian President Vladimir Putin will receive the overwhelming share of the blowback for his unprovoked assault on Ukraine, but Xi’s public declaration, coupled with Beijing’s continued diplomatic support for Moscow, has undermined China’s reputation and provoked renewed concerns over its global ambitions. Indeed, the intensifying war in Ukraine has already prompted calls for Taiwan to improve its defense capabilities and has given security partnerships such as NATO, the Quad, and AUKUS a renewed sense of purpose.

Xi’s ill-advised support for Moscow on the eve of Russia’s disastrous military campaign is not his first major foreign policy misstep. His decision to retaliate against EU officials last March in response to sanctions over human rights abuses in Xinjiang cost Beijing a long-coveted investment deal with Europe. His threats toward Taiwan are driving Washington and Taipei closer together and forcing other regional powers, such as Australia and Japan, to declare their own compelling interest in Taiwan’s security. And the Chinese military’s 2020 clash with the Indian army in the Galwan Valley galvanized hard-line opinion in New Delhi. These mounting failures highlight an increasingly evident trend: the more powerful Xi becomes and the more direct authority he exerts over Beijing’s foreign policy, the more adverse the outcomes are for China’s long-term strategic interests. After decades of relatively nimble and effective maneuvering by the post-Mao leadership, Xi has wrenched foreign policy in a new direction—one defined by a greater tolerance for friction with the United States, Europe, and neighboring powers and characterized by little internal debate or external input. What is taking shape is less China’s foreign policy than Xi’s.

With Xi set to assume a third five-year term as China’s leader at the upcoming 20th Party Congress, it is critical for the United States and its allies to understand not just the drivers and contours of his foreign policy but the political and bureaucratic ecosystem in which he makes decisions. As Putin’s reckless gambit in Ukraine has proved, an autocratic leader surrounded by sycophants and fueled by historical grievances and territorial ambitions is a menacing prospect. Xi is not Putin, and China is not Russia, but it would be unwise to ignore the growing parallels.

THE STRONGMAN

To say that Xi has consolidated power in China is to state the obvious. Few dispute that Xi holds a singular position within China’s bureaucratic apparatus, and it is increasingly hard to deny that something akin to a personality cult is developing in state media and other propaganda channels. Yet the implications of this reality are insufficiently appreciated, especially its impact on the behavior of the Chinese party-state.

Consider a pattern that has emerged across authoritarian political systems in which leaders remain in office far longer than their democratic and term-limited counterparts. The longer a leader stays in power, the more state institutions lose their administrative competence and independence as they evolve to fit that leader’s personal preferences. Successive rounds of purges and promotions shape the character of the bureaucracy, moving it incrementally in the same direction as the leader’s grand vision. What might begin as formal punishment for explicit opposition to the leadership eventually becomes a climate of informal self-censorship as members of the bureaucracy come to understand the pointlessness of dissent and grow better attuned to unspoken expectations of compliance. The leader also becomes more distant and isolated, relying on a smaller and smaller group of trusted advisers to make decisions. Most of those individuals remain at the table because they display absolute loyalty.

This small circle, in turn, acts as the leader’s window to the world, leaving much dependent on how accurate a depiction of external reality its members choose to provide. Such an opaque decision-making process makes it difficult for external observers to interpret signals from the central leadership. But even more crucially, it makes it hard for actors within these autocratic systems to anticipate and interpret their leaders’ actions. The result is an increasingly unpredictable foreign policy, with the leader formulating snap decisions in secret and the rest of the bureaucracy racing to adapt and respond.

Xi is not Putin, and China is not Russia, but it would be unwise to ignore the growing parallels.

The obvious parallel in the Chinese case is Mao Zedong, who oversaw a tortuous hollowing out of China’s nascent political and administrative institutions. Subservience to Mao defined the bureaucracy, and promotions were based on ideological correctness. Although other actors influenced Beijing’s foreign policy, notably Premier Zhou Enlai, the most important factor shaping China’s strategic behavior was Mao’s personal opinion. But identifying Mao’s dominance over China’s bureaucracy did not by itself provide clues about future foreign policy decisions. Mao’s belief in global revolutionary struggle led him to support armed movements in Southeast Asia, and his sense of realpolitik led him to normalize relations with the archcapitalist United States just a few years later. The key point with Mao’s foreign policy, as it is today with Xi’s, was that external observers needed to be attuned to his worldview, his ambitions, and his anxieties if they were to understand, anticipate, and survive his moves.

Xi, of course, is not Mao. He has no desire to foment global revolution, and his view of the proper domestic political order is far more conservative than Mao’s was. It is also important to note that internal opposition to Xi’s increasingly nationalistic and bellicose foreign policy clearly exists and is likely to grow as his decisions take their toll on China’s interests. But at the same time, there is little a would-be opponent can do to meaningfully constrain Xi—such is the level of overwhelming political and bureaucratic authority he now wields. His supporters occupy positions at the apex of all of the state’s power centers, including the military, the domestic security sector, and the state-owned economy. Xi does not run China’s political system alone, but as in Putin’s Russia, the consolidation of personalized authority over an extended period of time has rewired the decision-making processes in favor of the incumbent and his advisers. As a result, on issues ranging from Taiwan to Ukraine, the entire political system in China waits for Xi’s orders. Foreign policy in the 20th Party Congress period, which lasts from 2022 to 2027, will therefore be driven by Xi’s subjective view of international events and the increasingly isolated decision-making ecosystem that surrounds him.

A TEAM OF SYCOPHANTS

What might this new era look like? On a practical level, it will feature the continued marginalization of the government’s externally facing bodies. Consider the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. On paper, the MFA should be a vital conduit for understanding the actions and the intentions of China’s senior leadership on foreign policy. Indeed, this is why the MFA’s daily press conference was historically seen as important, as it was one of the few windows outside observers had into Beijing’s thinking. In practice, however, the MFA is increasingly scrambling to interpret signals coming down from Xi’s office, as evidenced by its frequently shifting day-to-day talking points on the Ukrainian crisis. The same dynamic exists within the Taiwan Affairs Office, which is, on paper at least, responsible for cross-strait policy. It has become apparent in recent years that the TAO is often blindsided by Xi’s decisions and left scrambling to both interpret and then implement his policies. It will be important to understand the functional realities of such bureaucratic marginalization moving forward, as statements by the Chinese government may not always accurately reflect Xi’s views. More important than traditional bureaucracies will be opaque and secretive bodies such as the National Security Commission and the various “leading small groups” that Xi commands.

Xi’s circle of advisers will also continue to shrink. Although it is not uncommon for leaders in any political system to prize the counsel of a select few voices, effective decision-making demands that these advisers bring competing points of view. There is still much to learn about how Putin came to believe that he could achieve a quick victory over Ukraine, but early signs indicate that his military advisers misled him about the true state of the Ukrainian army. This is a tragic reminder of how critical accurate information is to any political organization, especially in more closed and authoritarian systems. From what analysts understand, Xi’s confidants, including Li Zhanshu, Ding Xuexiang, and Wang Huning, are formidable bureaucratic actors, but there is no indication that they challenge his judgments or priors. And as some of these senior officials retire, Xi will be increasingly surrounded by younger, more inexperienced, and more pliant senior leaders. What Xi needs is a team of rivals. What he has now and will likely have in the future is a group of yes men.

Xi’s outlook on China’s security environment in the coming decade is increasingly pessimistic.

Then there is the critical issue of Xi’s worldview. It is becoming clear from his speeches and articles that Xi’s outlook on China’s security environment in the coming decade is increasingly pessimistic. As he said recently, “the international situation continues to undergo profound and complex changes,” adding that “the game of major powers is increasingly intense, [and] the world has entered a new period of turbulence and change.” The United States, Xi believes, has formalized a policy of containment toward Beijing. When Washington speaks of working with “allies and partners,” Xi hears echoes of Cold War–era encirclement, enacted through what he calls “exclusive small circles [and] blocs that polarize the world.” This diagnosis arguably led Xi to draw closer to Putin and Moscow in the months leading up to their meeting in February and is why he will not abandon Russia moving forward.

But it is not just pessimism that animates Xi’s worldview; it is a strong sense of nationalism, fueled by his confidence in the Chinese Communist Party’s economic and military power and his dismissive attitude toward the cohesion and stability of the United States and other democracies. Although it is arguably true that Beijing has overemphasized a narrative of U.S. decline for domestic propaganda purposes, Xi’s actions nevertheless indicate that he is comfortable asserting Beijing’s interests even when they clash with the capabilities and resolve of the United States and its allies. There are numerous examples of this dynamic, from China’s evisceration of Hong Kong’s democratic institutions to its ongoing campaign of economic coercion against Australia. The point here is less that Beijing adopts these confrontational policies without paying a price (it does) but rather that Xi’s risk tolerance appears to have grown in response to his shifting assessments of the global balance of power.

The combination of an unconstrained and nationalist autocrat who harbors an increasingly bleak view of the external environment makes for a potentially volatile period ahead. China’s position in global affairs is far more consequential today than it was during the Mao era. The international environment in which Xi attempts to steer Chinese interests is also significantly different from what it was in the 1960s and 1970s. Without the relative predictability of Cold War–era bipolarity, competition today is more complicated and harder to navigate. To compensate, the United States and its allies must prioritize direct communication with Xi to ensure that alternative ideas puncture his leadership bubble. It will also be critical for the leaders of like-minded countries to convey consistent messages during their own separate interactions with China’s leadership. After all, it is one thing for Xi to dismiss Washington as stuck in a “Cold War mentality” but another to ignore a broad coalition of democratic allies. Over the past four decades, China has repeatedly shown that it can change course before it courts disaster. The question now is whether it can do so again under Xi.