Abstract: On January 20, 2022, the Islamic State launched a complex assault on Hasakah’s Ghwayran prison, a place in which thousands of its fighters had been held since the ‘defeat’ of its territorial caliphate in March 2019. The attack was the first time that the group had directly targeted a major detention facility in Syria since losing its last significant territorial toehold in Syria, notwithstanding the consistent calls for prison breaks that have been uttered by its leaders during the last three years.

Even though, according to the U.S. government, the attack failed to produce a large-scale prison break, it was, by a significant margin, the highest impact and most complex operation launched by the Islamic State in Syria since its territorial defeat. A complete dataset of the operation claims the Islamic State has published relating to Syria since March 2019 suggests Islamic State cadres in Syria may have been saving their energies to carry out a large strike, cutting through the notion that previous declines in operational activity were a sign of weakening or that the prison attack necessarily portends a resurgence. With its leader since 2019, Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurashi, removed from the battlefield in a U.S. military operation in Syria in February 2022, it remains to be seen whether the group will return to ‘normal’ operations syncopated by occasional ‘spectaculars,’ or escalate its campaign of violence as it attempts to demonstrate any immediate tactical gains it made at Ghwayran and, simultaneously, showcase its ability to weather the storm of leadership decapitation. The data suggests that whatever the monthly ebb and flow of Islamic State operations in Syria, the group remains a latent and persistent threat.

In the early hours of February 3, 2022, the leader of the Islamic State, Abu Ibrahim al-Hashemi al-Qurashi, died during a U.S. military operation in northwest Syria that followed months of surveillance.1 According to The Washington Post, “The picture of Qurayshi that emerged from the surveillance is that of a hands-on commander who was firmly in charge of his organization […] His intensive involvement in operational planning made Qurayshi especially dangerous, officials said.”2 a However, in the course of his two and a quarter years as caliph, al-Qurashi refrained from making any audio or video appearances, limiting his ability to provide strategic guidance to followers and making it unclear, at least at present, what the impact of his loss will be on the broader Islamic State movement.

For the Islamic State, though, all caliphs are important, and al-Qurashi’s death was unequivocally a major symbolic blow.3 It was not just the fact that U.S. forces had managed to identify and locate the most reclusive leader of the movement to date; it was that the raid came two weeks to the day after what was, as this article demonstrates, easily the Islamic State’s most significant and impactful operation in Syria since well before its territorial defeat in 2019, an event that had energized its global cadres and in-country networks in a manner not been seen in years.4

The assault—which al-Qurashi was deeply involved in the planning of, per U.S. officials quoted by The Washington Post5—started when, on January 20, 2022, a vehicle bomb struck the gates of Ghwayran prison in the city of Hasakah, a place in which thousands of Islamic State fighters had been detained since March 2019 when the last vestiges of the group’s territorial proto-state were routed by the global coalition and its local allies.6 This attack—which coincided with a multi-pronged assault by Islamic State sleeper cells, an insurrection inside the prison, and a separate bombing at a nearby fuel depot—facilitated the escape of a large (though unconfirmed) number of militants and left hundreds dead and injured, before ultimately descending into a week-long siege.7 While it was still ongoing, the Islamic State went to painstaking lengths to demonstrate that this was not just ‘another’ attack in Syria. Rather, it framed it as a new ‘malhama’ (‘epic battle’), the latest episode in its apocalyptic war against the enemies of Islam and something akin in significance to the pitched battles of Mosul, Raqqa, the Libyan town of Sirte, and Marawi in the Philippines.8

As of the time of publication, it remains unclear how many of Ghwayran’s Islamic State inmates were able to escape. Autonomous Administration (AA) sources reported minutes after the first bombs went off that 20 had fled the prison, though this claim was walked back later that evening.9 The following morning, a spokesman for the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) announced that SDF security officials had detained some 110 inmates in the immediate vicinity of the prison and stated that the clean-up operation was ongoing.10 On February 3, The Washington Post reported that by the time the prison was back in the hands of the SDF, “scores, maybe hundreds, of prisoners had escaped, free to raise the Islamic State’s black flag and fight again.”11 Meanwhile, Islamic State sources on Telegram have claimed that hundreds managed to break out, including “three senior leaders,” a number that was later revised up to 800 by the Islamic State’s Central Media Diwan.12 However, there is no independent evidence to back the Islamic State’s claims that so many escaped, and such claims need to be treated with extreme caution; U.S. national security advisor Jake Sullivan stated on January 30 that the group had “failed in its efforts to conduct a large-scale prison break to reconstitute its ranks.”13

In the weeks since, the Islamic State has hailed the Ghwayran siege as a major strategic breakthrough for its insurgent prospects in Syria, with some of its supporters even going so far as to claim that it more than outweighed the death of al-Qurashi, the movement’s elusive leader.14 b This article assesses the extent to which that is the case, considering in detail its operational trajectory in the country to date by drawing on a complete dataset of all Islamic State attack reports published from Syria since March 2019, the month during which the group lost its last significant territorial foothold in the country.

Even though these reports are, by definition, propagandistic in nature, the U.S.-led Combined Joint Task Force Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR) has itself stated that they are ‘largely accurate’ as an indicative measure of Islamic State activity.15 Moreover, separate research by this author and others has determined that, if anything, the Islamic State underreports in Syria, not overreports.16 An as yet unclaimed bombing near Ghwayran prison on December 19, 2021—that is, almost one month exactly before the January assault—could be one potentially highly relevant example of this deliberate underreporting dynamic.17 It is conceivable that, if the Islamic State was indeed behind this incident—which was the first explosive device detonated in Hasakah city in 2021—it was testing the waters to see how quickly the SDF was able to respond, but in a manner that did not draw attention to its capability in the city, which, as discussed below, was assumed to be lacking on account of its prolonged inactivity there. On that basis, it would make strategic sense for it to refrain from issuing an official claim regarding the incident.

In any case, this broad indicative accuracy means that, provided that they are only treated as strategic indicators of trends—as they are below—and not as definitive evidence of specific operations, the collective utility of these data points is significant. The analysis proceeds as follows. First, there is an overview of the Ghwayran prison attack itself, which draws on both the Islamic State’s own account of the assault and the accounts of several non-Islamic State sources in northeast Syria, including that of the SDF. After that, the authors outline the data collection methodology before then using this data to consider the broader strategic context within which the operation occurred, weighing up just how significant or unusual it was for the Islamic State to conduct an attack of this kind.

When considered in aggregate, the data clearly attests to the fact that the Ghwayran prison attack was not simply ‘par for the course’ for the Islamic State within Syria. However, the data also cuts through the idea that it was the result (or the beginning) of a new period of resurgence for its network in the country. Instead, the data shows that the Islamic State never went away; rather, it has been a persistent and capable actor in the Syrian security landscape, especially in the northeast, throughout the time that has elapsed since its ‘defeat’ at Baghuz in 2019, which was wrongly hailed by the SDF at the time as the “total elimination of [the] so-called caliphate.”18 On that basis, the article concludes by discussing what may be next in Syria for the Islamic State, especially now that al-Qurashi—its leader since late 2019—has been killed: either a return to ‘normal’ operations syncopated by occasional ‘spectaculars’ or a period of heightened violence as it attempts to demonstrate any immediate tactical gains it made at Ghwayran and, simultaneously, showcase its ability to weather the storm of leadership decapitation.

The Attack

According to the SDF, the Ghwayran attack started when a car bomb struck the main gate of the prison just after 7:00 PM local time on January 20, 2022, which enabled several cells of Islamic State fighters to infiltrate the complex.19 Simultaneously, thousands of inmates inside Ghwayran rioted, ultimately overpowering the guards and enabling some to barricade themselves in to defend against a counterattack and others to escape. The SDF claimed that these efforts were aided by the arrival of “a large cargo car [sic] loaded with weapons and ammunition” and a tunnel complex that “had been dug inside some houses” in the area.20

The Islamic State’s account is similar, albeit with some additional details.21 It held that the prison assault began when two foreign fighters detonated suicide bombs (or, perhaps, a tandem vehicle bomb; the particular device was not specified) outside its gates, enabling two three-man cells of inghimasi operatives—essentially, special forces-style fighters equipped with suicide belts—to enter the prison and facilitate a breakout from within. Simultaneously, another three-man inghimasi cell was dispatched to attack an oil depot in the immediate vicinity of the prison to create a smokescreen to obstruct coalition intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities, with a fourth assaulting a nearby SDF base to obstruct any immediate attempt at a counterattack. In contrast with the SDF’s account, no mention was made of an arms-laden vehicle arriving in support of the insurrectionists, let alone a tunnel complex. Rather, the Islamic State claimed that the siege occurred as it did because its rioting supporters had been able to seize a weapons and ammunition store inside the prison after overpowering its guards, in the process taking dozens of hostages and opening up stable channels of communication with the Islamic State (including its Central Media Diwan, which subsequently went on to publish some six videos from inside the prison complex).22

A protracted battle ensued in the days that followed, with hundreds of inmates taking up arms against the SDF and, reportedly, U.S. and British special forces.23 To try to lighten the pressure those inside the prison complex were facing—as well as to delay or undermine the ‘People’s Hammer’ clean-up operation that was launched by the SDF to recapture escapees—Islamic State cells across northeast Syria, including in both Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor governorates, simultaneously launched dozens of other attacks, some sophisticated and others seemingly more opportunistic.24 Reportedly, it was not long, however, before food and ammunition stocks ran out for the insurrectionists, which prompted them to open up a line of negotiations with the SDF, using the lives of the hostages they had taken to bargain for medical support and, ultimately, their own lives.25 On January 26, 2022, after seven days of intensive fighting and dozens of coalition air raids, the siege abruptly broke when hundreds of Ghwayran’s inmates surrendered, leaving a few small pockets of resistance to fight to the death in its northern wards.26

All in all, the Ghwayran prison attack was totally out of step with what had emerged as the Islamic State’s ‘normal’ style of operations in Syria in the years leading up to it. As the next section demonstrates, the prison attack had significantly more impact, as well as more moving parts, than any other attack or campaign deployed by the group in Syria since March 2019. Notwithstanding the questions that remain regarding its overall impact—above all, how many actually escaped in the end, and who they were—this alone attests to the attack’s strategic significance for the movement, which is assessed in more detail below.

Methodology

The dataset on which this assessment is based was collected exclusively from the Islamic State’s closed-access feed on Telegram, a social media platform that the group favors for propaganda distribution.27 In the August 2020 issue of CTC Sentinel, this author (Winter) wrote:

In 2019, two outlets [on Telegram] were charged with distributing all official Islamic State communications [in relation to its activities]: the Nashir network, which was tasked with disseminating materials produced by central and provincial media units; and the Amaq News Agency, which essentially acted as its newswire service. Operating alongside these was a separate, supporter-run dissemination hub called the Nashir News Agency. (note: despite the name, this entity is distinct from Nashir, which is internal to the Islamic State.) [Throughout 2019,] the Nashir News Agency aggregated all posts from both Nashir and the Amaq News Agency on a minute-by-minute basis.28

As of February 2022, this description of the Islamic State’s propaganda and attack report distribution network remains true. Accordingly, it was from the Nashir News Agency that the dataset used for the present analysis was drawn, with a handful of additional ‘exclusive’ reports being collected from Al Naba, the Islamic State’s newspaper, which the Nashir News Agency also publishes. Al Naba ‘exclusives’ are attacks that are not reported elsewhere by the Islamic State.

Once filtered so that it only contained Syria operation claims published since the defeat of the Islamic State at Baghuz in March 2019, this left 1,717 unique official attack reports relating to Islamic State activities in Syria (as of February 8, 2022), with each report corresponding to a single attack. Each of these claims was manually checked to make sure that no duplicate reports had found their way into the dataset. Once this had been done, they were inputted into ExTrac, an artificial intelligence-powered conflict analytics system co-founded by one of the authors (Winter), where they were automatically coded and analyzed according to several criteria, among them:

Week and date of attack (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4);

Lethality of attack (i.e., number of kills reported in each claim) (Figures 2, 3); and

Longitude and latitude of attack location (Figure 5).The incidents were also coded according to a number of details not visualized below, including weapons used in attack, attack type (i.e., ambush, assault, assassination, bombing, etc.), target (i.e., Syrian Arab Army, Syrian Democratic Forces, etc.), and target type (i.e., military, intelligence, civilian, government, etc.).

Operational Context

When the Islamic State’s claimed activities in Syria are considered in aggregate, it is clearly apparent that the Ghwayran attack was a major departure from its ‘normal’ trajectory in the country.

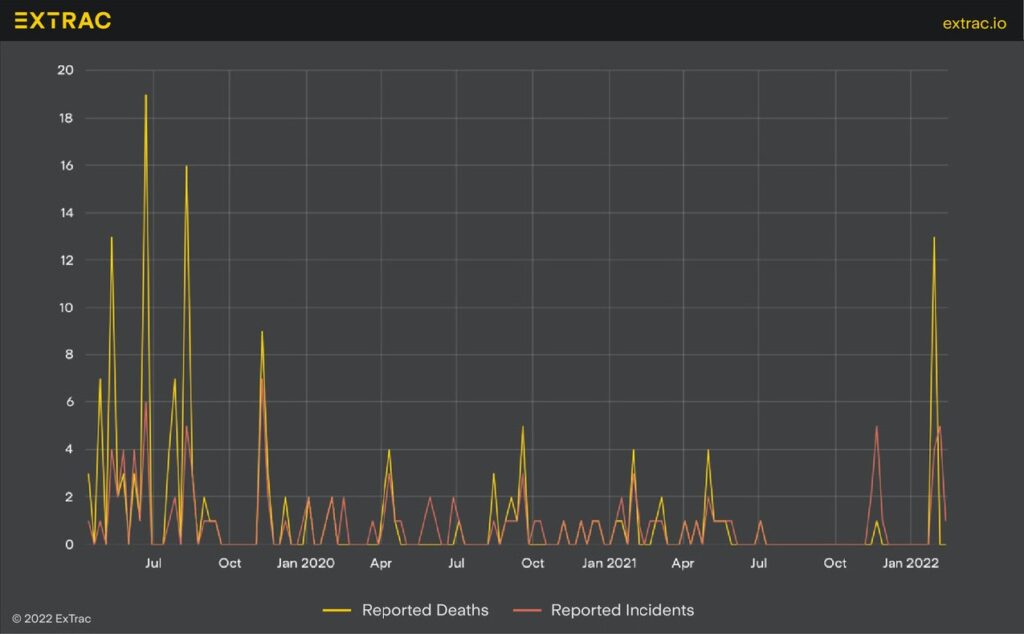

As Figure 1 shows, it was its first self-reported attack in Hasakah city since December 2019, when one of its fighters lobbed a hand grenade at members of the SDF in, incidentally, Ghwayran district.29

Figure 2, which visualizes all Islamic State self-reported incidents in Hasakah governorate (not just Hasakah city) since March 2019, further shows that the group had not claimed credit for an operation in the governorate since mid-summer 2021—aside, that is, from a short-lived surge in self-reported attacks in November 2021 that followed the foiling of a previous planned assault on Ghwayran prison (discussed in more detail below).

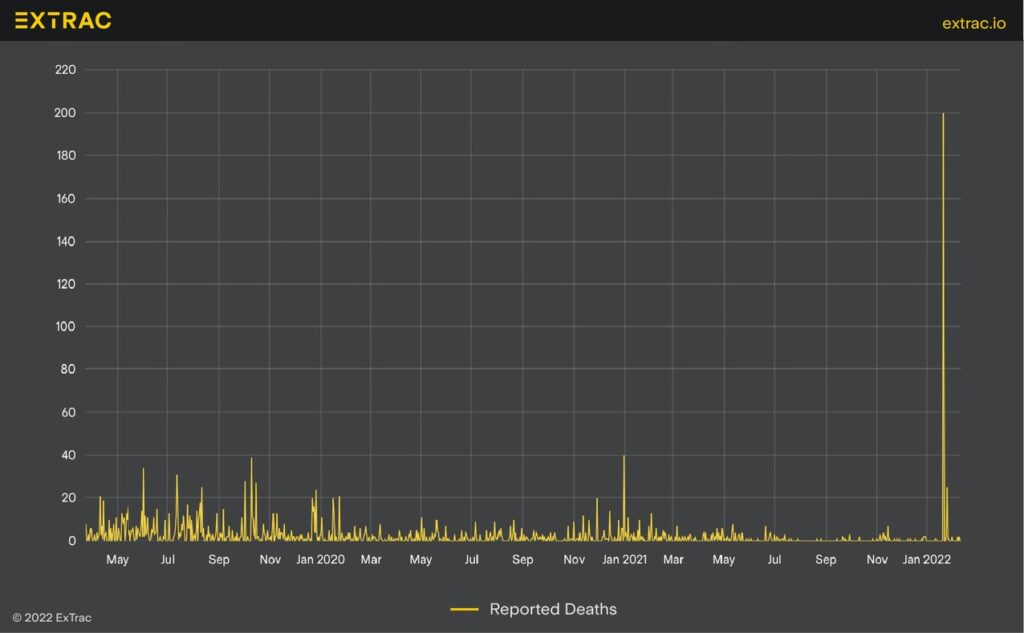

Figure 3 shows all the deaths the Islamic State claimed it caused across the whole of Syria since March 2019. It indicates that, by the Islamic State’s own metrics, the Ghwayran assault was its most deadly attack in Syria by a factor of five.

This data is unambiguous. It shows that the Ghwayran prison attack and the campaign that followed occurred in a part of Syria from which the Islamic State had not reported regular activity in years, let alone months. Moreover, the metrics speak to the unusual scale of the Ghwayran attack, which was far out of step with what the Islamic State has typically been reporting from Syria in previous years.

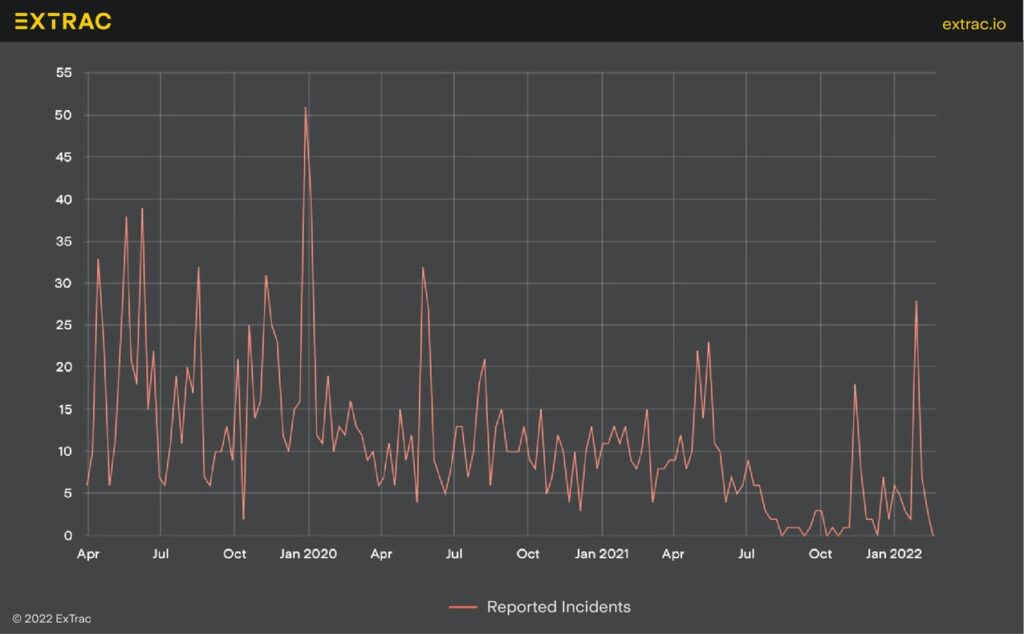

The anomalous nature of the incident does not stop there. When all the Islamic State’s Syria claims since March 2019 are taken into account (i.e., not just those from Hasakah city or Hasakah governorate), as is the case in Figure 4 below, the data shows that the prison assault occurred after a protracted lull in reported Islamic State activity in Syria. This lull dates back to July 2021, when, halfway through the month, there was a step-change in the number of attacks the Islamic State typically claimed on weekly basis. This saw its average monthly rate of reporting drop from around 50 claims a month to just five claims a month—and sometimes fewer.

At the time that it occurred, the reason for this precipitous and sustained decline was not clear. It could, for example, have simply been an indication that the Islamic State’s capabilities were at a low ebb due to sustained SDF security operations. However, in view of the two sophisticated prison break attempts the group staged just weeks apart—with the first, which is discussed below, failing in November 2021 and the second succeeding in January 2022—it seems more likely that it was symptomatic of a decision by the group’s leadership to lay low and prepare.30

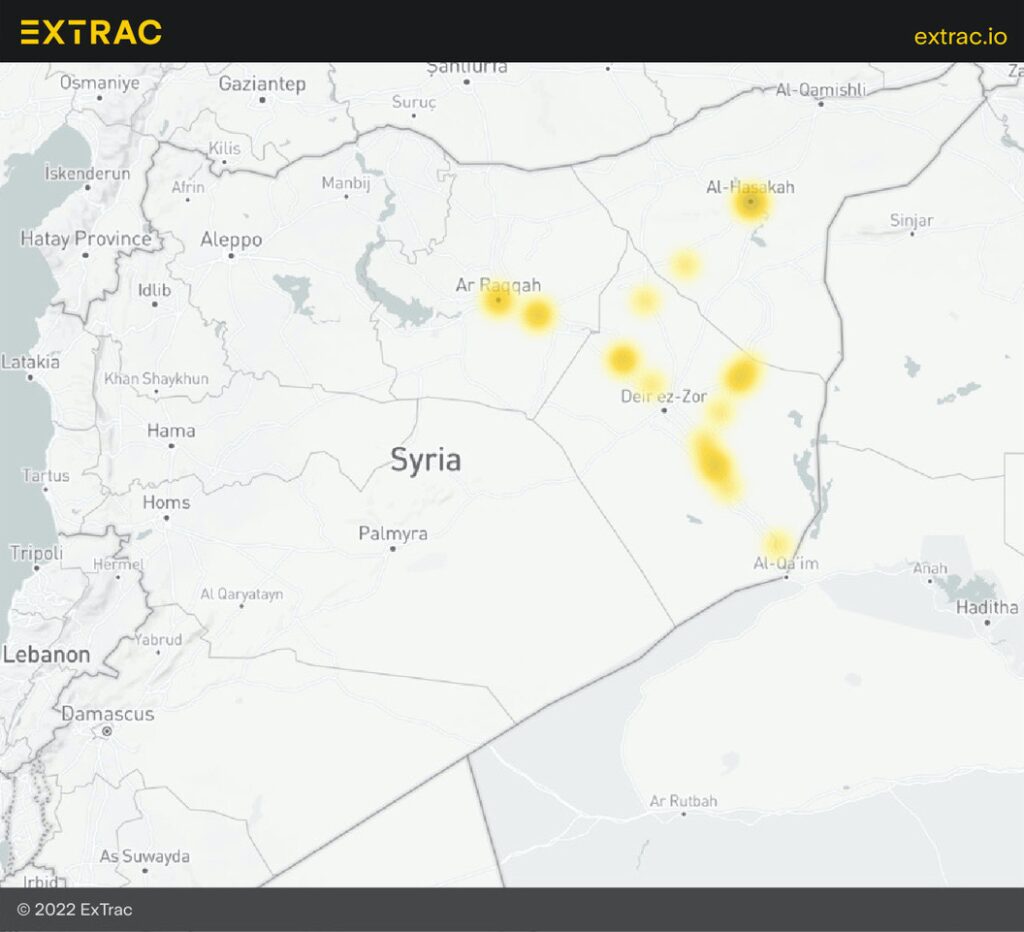

The idea that this apparent operational change came about because the Islamic State had opted to lay low so it could stage less regular but more impactful campaigns is even more plausible when the November 2021 surge in self-reported attacks is compared with prevailing trends over the course of the previous four months. (See the second-most recent spike in Figure 4.) As mentioned, this November 2021 surge, which was widely corroborated by non-Islamic State sources at the time,31 occurred immediately after an SDF operation to dismantle an Islamic State cell in Deir ez-Zor governorate that was believed to be plotting an imminent operation on Ghwayran prison. (Notably, the failed plot—like the successful attempt two months later—would have involved several cells and suicide bombers.32) When it was foiled, northeastern Syria lit up with Islamic State activity. Indeed, in the space of a few days in November 2021, the group claimed more attacks than had been reported in the previous three months combined. Almost exactly the same pattern played out after the prison assault in January 2022, which is visualized in the most recent spike in Islamic State self-reported attacks in Figure 4 and also in the heatmap (Figure 5), which shows the geographic distribution of Islamic State self-reported attacks in Syria while the Ghwayran siege was ongoing. It is notable with regard to this spike in operations that, according to The Washington Post, “the flow of messengers” to al-Qurashi’s house in Syria increased after the prison attack.33

Based on this clear latent capability—which, considering these surges happened twice in quick succession, suggests both robust covert networks and access to significant munitions stockpiles—it is likely that the decline in Islamic State-reported operations witnessed since July 2021 was a strategic decision by the group rather than constraints forced on it. If this is indeed the case, then it is critical that the threat posed by the Islamic State’s networks in Syria is not overlooked, no matter how ‘quiet’ it goes when reporting dries up.

Conclusion

The Ghwayran attack was the first time that the Islamic State directly targeted a major detention facility in Syria since it lost its last territorial foothold in Syria in 2019, notwithstanding the consistent calls for such attacks that have been uttered by its leaders in every major policy statement since its defeat at Baghuz three years ago.c As previous analysis published in CTC Sentinel has shown,34 Islamic State affiliates elsewhere have targeted prisons a number times in recent years—orchestrating mass prison breaks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in October 202035 and Afghanistan in August 202036—but aside from one assault on October 17, 2019, on a temporary detention facility in western Raqqa governorate, the group had until January 2022 refrained from launching any such attacks in Syria since its territorial defeat.37 This is likely due to the fact that, in contrast to the eastern DRC or Afghanistan, the prisons in northeastern Syria that hold Islamic State supporters have been heavily guarded by the SDF with support from the global coalition. Accordingly, any attempted breakout from one of them was always very likely to be met with a protracted, intensive response.

The fact that al-Qurashi—who, per U.S. President Joe Biden, was “responsible” for the prison assault38—and his inner circle thought that the time was right for such a high-risk assault to go ahead, not once but twice (after the first plot failed), speaks volumes about their assessment of the insurgency in Syria. The reality is this attack would not have happened unless the Islamic State had been confident that its potential benefits would end up outweighing its potential drawbacks.

That is not to say, however, that the movement is on the cusp of a new period of ascendancy in Syria, especially now that its latest caliph has died. After all, there are several aspects that might have motivated the Ghwayran operation. One, of course, is the material goal of freeing inmates, a goal that served the Islamic State movement well during the ‘Breaking the Walls’ campaign in Iraq in 2012-2013, ultimately paving the way to its capture of Mosul in 2014.39 But Syria in 2022 is not Iraq in 2012 (it is not as permissive a security environment for the group), nor is the Islamic State today the Islamic State of Iraq then (its network in Syria is not as well-resourced, nor does it have anywhere near the same degree of freedom of movement). On that basis alone, the Ghwayran prison assault may have been judged unlikely by Islamic State leaders to result in hundreds of successfully exfiltrated escapees. So, some other consideration may have pushed the Islamic State to have calculated that this attack—an operation that was certain to result in numerous deaths within its own ranks as well as a significant tightening of the security cordon in its aftermath—was worth it. Perhaps that calculation was based on its desire, or perceived need, to free a select few senior officials; or perhaps it was driven by a desire, or perceived need, to shake things up and demonstrate that three years after the collapse of its proto-state, it remains a relevant and capable actor in the Syrian war.

Whatever the case, moving forward, with its leader since 2019 now removed from the battlefield, it remains to be seen whether the Islamic State’s network in Syria will return to ‘normal’ operations syncopated by occasional ‘spectaculars’ or, perhaps in tandem with its network in Iraq, escalate its campaign of violence as it attempts to demonstrate any immediate tactical gains it made at Ghwayran and, simultaneously, showcase its ability to weather the storm of leadership decapitation.

Any such ramp-up across the two countries will face challenges. Given al-Qurashi’s reportedly deep involvement in operations, it is possible his death will, at least in the short term, put a dent in the group’s ability to plan major attacks. “This guy was working it,” a former senior intelligence official told The Washington Post, which also reported that his underground network “included dozens of cells scattered across Syria and Iraq.”40 In light of what The Washington Post reported was a “trove of intelligence” collected in the surveillance that preceded the operation against al-Qurashi, “as couriers were tracked and subsequently monitored as they met with contacts in other parts of Iraq and Syria,” these cells are now in a far more precarious position than they were before. Whether that means they go to ground for the near-term remains to be seen, but a series of complex Islamic State attacks in Syria during the second week of February 2022—one of which resulted in five SDF deaths41—suggests otherwise.

That being said, such momentary surges do not necessarily indicate overall strength and, according to a U.N. report published in February 2022, “In Iraq, ongoing counter-terrorism pressures have yielded positive results in reducing ISIL activities.”42 Recent data analysis of Islamic State attacks in Iraq by Michael Knights and Alex Almeida published in the January 2022 issue of CTC Sentinel corroborates this, “showing an insurgency that has deteriorated in both the quality of its operations and overall volume of attack activity, which has fallen to its lowest point since 2003” with the group “increasingly isolated from the population, confined to remote rural backwaters controlled by Iraq’s less effective armed forces and militias, and [lacking] reach into urban centers.”43 Yet, the United Nations stressed that the Islamic State “continues to operate as an entrenched rural insurgency” in both Iraq and Syria,44 and Knights and Almeida noted that “analysts should leave a wide margin that some fraction of the Islamic State’s decline in Iraq is, in fact, dormancy or latency that could be reversible under the right conditions.”45

In Syria, the Ghwayran prison attack was an example of the latent threat posed by the Islamic State exploding into view. Whatever the monthly ebb and flow of Islamic State operations in Syria, the group is likely to persist as a threat for the foreseeable future.