Abstract: Over the past 40-plus years, the Islamic Republic of Iran has targeted dissidents, Western opponents, Israelis, and Jews in assassination plots, abduction plots, and surveillance operations that facilitate both. Iran has carried out such external operations around the world, in countries with both strong and weak law enforcement agencies, border crossings, and intelligence services. It has done so consistently over the years, including at times and in places where carrying out such operations could undermine key Iranian diplomatic efforts, such as negotiations over the country’s nuclear program. This study, based on a dataset of 98 Iranian plots from 1979 through 2021, maps out key trends in Iranian external operations plotting.

In February 2021, a Belgian court convicted Assadollah Assadi, an Iranian diplomat based in Vienna, of organizing a July 2018 plot to bomb the annual convention of the National Council of Resistance of Iran—the political wing of the Mujahedeen-Khlaq, MEK—near Paris. Three accomplices, all Iranian-Belgian dual citizens living in Brussels, were also sentenced for their roles in the plot.1 According to German and Belgian prosecutors, Assadi was no run-of-the-mill diplomat but rather an Iranian intelligence officer operating under diplomatic cover. In a statement, prosecutors tied Assadi to Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS), whose tasks “primarily include the intensive observation and combatting of opposition groups inside and outside Iran.”2

The Paris plot appears especially audacious in its scope. The perpetrators intended to detonate an indiscriminate explosive device instead of carrying out a targeted assassination; Assadi smuggled TATP and a detonator onto a flight from Iran to Austria; the plot line included touch points in at least five European countries; and several prominent current and former government officials from the United States and other countries were present at the annual convention of the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI).3

Pointing to this case, the United States sought to mobilize its partners to counter Iran’s support for terrorism around the world. A senior State Department official summarized Washington’s concerns in a briefing for the press:

The most recent example is the plot that the Belgians foiled, and we had an Iranian diplomat out of the Austrian embassy as part of the plot to bomb a meeting of Iranian opposition leaders in Paris. And the United States is urging all nations to carefully examine diplomats in Iranian embassies to ensure their countries’ own security. If Iran can plot bomb attacks in Paris, they can plot attacks anywhere in the world, and we urge all nations to be vigilant about Iran using embassies as diplomatic cover to plot terrorist attacks.4

As it happens, the foiled Paris plot was just one in a string of Iranian operations carried out by Iranian operatives or their proxies. In June 2018, the Netherlands expelled two Iranian diplomats based at the Iranian embassy in Amsterdam following an investigation by Dutch intelligence.5 This move came just months after an Iranian Arab activist was gunned down in Amsterdam.6 In March 2018, Albanian authorities charged two Iranian operatives with terrorism after they surveilled a venue where Iranian Nowruz (New Year) celebrations were set to begin. In January 2018, German authorities raided several homes after weeks of surveillance confirmed they were tied to Iranian agents. These operatives were reportedly scoping out potential Israeli and Jewish targets in Germany, including the Israeli embassy and a Jewish kindergarten. Ten of the Iranian agents were issued arrest warrants, but none were apprehended.7

Weeks earlier, a German court convicted an Iranian agent for spying after he scouted targets in Germany in 2016, including the head of the German-Israeli Association. The German government subsequently issued an official protest to the Iranian ambassador.8

Perhaps most disturbing, however, is the fact that Iranian assassination, surveillance, and abduction plots continued unabated despite the negative publicity that accompanied the arrest of Assadi and his accomplices. At least 26 well-documented such plots have occurred in the three years since the Paris plot in places as far afield as Colombia, Cyprus, Denmark, Dubai, Ethiopia, France, Germany, Iraq, Israel, Kenya, the Netherlands, Scotland, Sweden, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States, according to a dataset maintained by the author. This includes the plot exposed in July 2021 to kidnap New York-based journalist and human rights activist Masih Alinejad, a U.S.-Iranian dual citizen, and forcibly take her to Iran where “the victim’s fate would have been uncertain at best,” in the words of U.S. Attorney Audrey Strauss.9 Since then, authorities have identified Iranian plots in Colombia (September 2021),10 Cyprus (October 2021),11 Kenya (November 2021),12 Tanzania (November 2021),13 and Turkey (September 2021, February 2022).14

Iranian agents and their proxies have targeted dissidents and perceived enemies for assassination, surveillance, and abduction in plots around the world since the earliest days of the Iranian revolution. The first such case in the United States took place in July 1980 when Iranian agents recruited David Belfied (aka Dawud Salahuddin), an American convert to Shi`a Islam, to assassinate former Iranian diplomat Ali Akbar Tabatabai in Bethesda, Maryland.15 Later, in a 1997 U.S. State Department briefing, Ambassador Philip Wilcox stated that, “since 1990, we estimate and indeed, we have solid information for, that Iran is responsible for over 50 murders of political dissidents and others overseas.”16

But while the Islamic Republic of Iran has a long history of engaging in operations such as these, it appears to have picked up the pace over the past decade (2011-2021) and exhibited multiple patterns worth drawing out. Several milestone events in recent years underscore the need to better understand trends in Iranian assassination, surveillance, and abduction operations. Most significantly, the January 2020 targeted assassination of General Qassem Soleimani, the head of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ Quds Force (IRGC-QF), along with Iraqi Shi`a militia leader and designated terrorist Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, clearly increased the risk of Iranian retaliation or escalation. To date, Iran has primarily responded to this incident through efforts targeting U.S. forces in Iraq. But days after the Soleimani strike, U.S. intelligence and law enforcement agencies released a joint intelligence bulletin warning of the need “to remain vigilant in the event of a potential [Government of Iran] GOI-directed or violent extremist GOI supporter threat to US-based individuals, facilities, and [computer] networks.”17 Other milestone events making this issue all the more timely include matters such as negotiations over the possible reentry of the United States into a renegotiated nuclear deal with Iran (an updated Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, JCPOA); the potential for Iran to lash out over the economic consequences of international sanctions; Iran’s aggressive regional posture in places such as Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and the Strait of Hormuz and Persian Gulf; domestic, political, economic, and environmental tensions within Iran; and the looming prospect of selecting a new Supreme Leader as Ali Khamenei ages.

This study draws on an unclassified and open-source dataset of 98 cases of Iranian external operations from December 1979 through December 2021. The dataset draws on court documents, reports, press releases, and news articles, and is therefore, by definition, limited to what information is publicly available. Some of that information may be misleading or wrong; much of it is likely to be incomplete—such is the nature of compiling open-source datasets—and this is in no way a comprehensive listing of all such Iranian external operations. Additionally, there is significant overlap between different analytical categories in this dataset. For example, a plot may have involved surveillance and abduction, or may have been carried out by a combination of Iranian and non-Iranian operatives.

In an effort to capture a broad array of Iranian foreign operational trends, the dataset includes assassination plots targeting specific persons, indiscriminate attacks targeting groups of people such as dissidents or a foreign embassy, abduction plots aimed at bringing an individual to Iran against their will, and surveillance operations aimed at supporting such activities or collecting intelligence for future potential operations. The dataset includes cases involving both Iranian operatives and proxies, but it does not include every case in which an Iranian proxy group—such as Lebanese Hezbollah—carried out an attack unless the attack was carried out jointly with Iran or there is convincing evidence that the proxy specifically carried out the attack at Iran’s behest. It also does not include militant attacks such as Hezbollah rocket salvos fired at Israeli civilian communities.

This study looks back at Iranian external operations since the Iranian revolution, but in an effort to provide timely analysis, it then focuses more closely on Iranian external operations over the past decade (2011-2021). The study examines in turn the who (targets and perpetrators), the what (types of attacks), the how (tactics), the where (location) and, in more general terms explained later, the when and why (timing and motives) behind Iranian external operations. The study then forecasts potential future trends in Iranian external operations worthy of consideration. The observations that follow are all drawn from analysis of the author’s dataset.

Over the past several decades, Iranian external operations of the kinds described above fall into several functioning subgroups: the targeting of dissidents, the active execution of religious edicts (fatwas) against entities perceived as insulting the Islamic faith, the targeting of perceived enemies, and the targeting of Jews. Several of these categories overlap, such as the targeting of Jews and Israeli citizens or diplomats.

Iran has employed a range of actors in its operations, including its own agents, proxies, criminal recruits, and a combination of the above. On occasion, Iran has successfully inspired loyalists from around the world to act on its behalf, such as the attacks following Ayatollah Khomeini’s fatwa calling for the assassination of Salman Rushdie, predating today’s general trend toward lone-offender attacks.18 Over the decades, Iran has displayed a willingness to employ explosives in its attacks, and in recent years in its assassination plots as well. In the early years after the 1979 revolution, Iran instituted a major crackdown on dissidents and former officials at home and abroad. In the past few years, Iran has intensified a similar campaign targeting dissidents, likely in response to perceived regime instability or threats at home and the success of some dissident groups in carrying out attacks in Iran or publicly exposing elements of the Iranian nuclear program. Over time, Iran has added cyber activities to its operational toolkit, deploying cyber capabilities to spy on dissidents, surveil its enemies19 and engage in disinformation campaigns.20

Perhaps contrary to conventional wisdom, Iran has conducted external operations around the world, including in countries with advanced law enforcement, border security, and intelligence services. While Iran is known to exploit less advanced security services in places like Eastern Europe, central Asia, and Africa, it has continued to plot attacks and enhance its surveillance capabilities in Europe and the United States where the operating environment is more difficult.21 At times, the cases in question can be further separated by motive, such as revenge for support of Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War or escalation of Iran’s shadow war with the West over the Islamic Republic’s nuclear program prior to the JCPOA. In other cases, attributing a specific motive is more difficult, particularly when working only with open-source materials. However, careful examination of the perpetrators, targets, methods, locations, timings, and potential motivations of such attacks sheds light on Iran’s current operational environment and assists in forecasting its potential future plots.

One theme that stands out is Iran’s willingness to carry out such operations, typically in a manner the regime believes will grant it some measure of deniability, even against the backdrop of sensitive negotiations with Western powers such as negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program and removal of international sanctions.

WHO? – Targets and Perpetrators of Iranian External Operations

Targets of Iranian External Operations

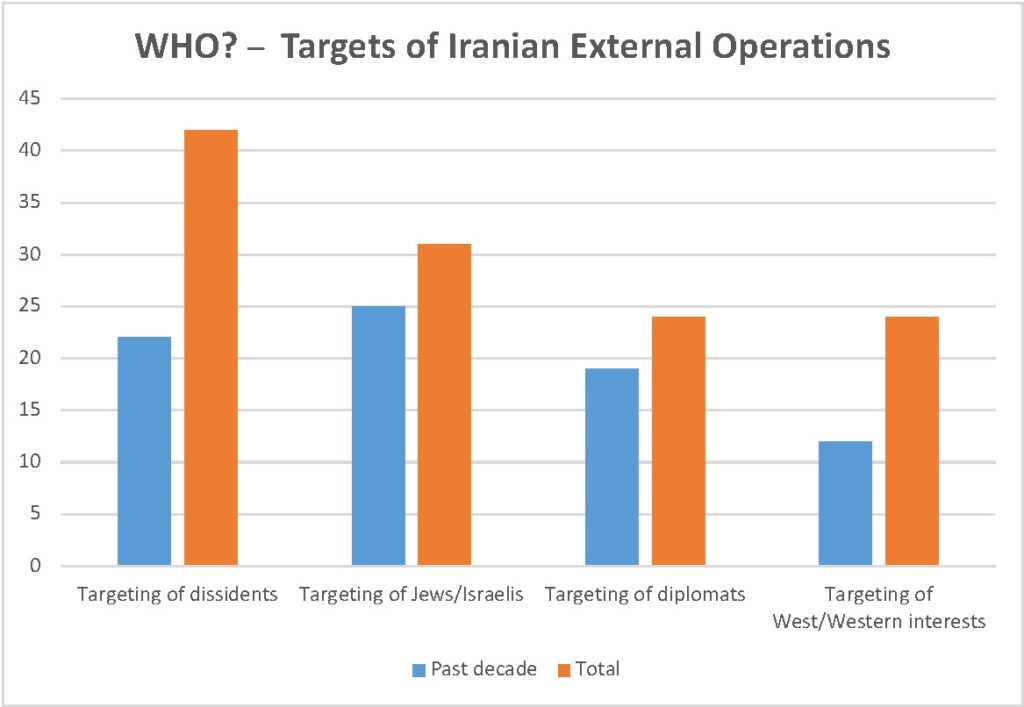

Of the 98 cases in the dataset, 42 involved the targeting of dissidents, 21 of whom were dual nationals or legal foreign residents. An additional 31 of the 98 cases targeted Jews or Israelis, 24 targeted diplomats, 24 targeted Western interests, seven targeted Gulf state interests, five involved the fatwa against Salman Rushdie, and two appear to be incidental to the primary target. (For example, in Baku, Azerbaijan, the Israeli embassy was located in the same building as the Japanese embassy.)

Limiting the analysis to the past decade, the numbers remain alarming. Out of 55 cases over the past decade, 22 operations targeted Iranian dissidents, 25 cases targeted Jews or Israelis, 19 targeted diplomats, 12 targeted specifically Western interests, and six targeted Gulf state interests.

Targeting Iranian dissidents has been a constant feature of Iranian external operations. Immediately after the founding of the Islamic Republic, the new Iranian leadership spearheaded an assassination campaign aimed at individuals the regime determined were working against its interest. The CIA found that between 1979 and 1994, Iran “murdered Iranian defectors and dissidents in West Germany, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and Turkey.”22 In total, the new regime targeted over 60 individuals in assassination attempts.23 Often, these plots involved members of Hezbollah, who served as logistics experts or gunmen.

The September 1992 Mykonos restaurant attack in Berlin targeting Iranian-Kurdish opposition leader Dr. Sadegh Sharafkandi may be the most infamous incident, but the one that appears to have most shaken the Iranian expatriate community at the time was the August 1991 assassination of Chapour Bakhtiar, a former Iranian prime minister and secretary-general of the Iranian National Resistance Movement. On August 6, 1991, Iranian operatives stabbed Bakhtiar and an aide to death in Bakhtiar’s Paris apartment.24 In July 1980, another assassination attack targeting Bakhtiar led by Anis Naccache ended up killing a policeman and Bakhtiar’s female neighbor. After Naccache was imprisoned in France for the attempted killing, Hezbollah frequently demanded his release when abducting French citizens in Lebanon.25 In a 1991 interview, Naccache spoke about his experience conducting external operations for Iran, explaining: “I had no personal feelings against Bakhtiar … It was purely political. He had been sentenced to death by the Iranian Revolutionary Tribunal. They sent five of us to execute him.”26

Over the past decade, Iranian agents and proxies continued to target Iranian dissidents. Indeed, 22 out of the 42 Iranian cases targeting dissidents in this dataset occurred within the past decade. Of these 42 cases in the overall data set, 21 (12 in the past decade) targeted dissidents who were dual nationals or legal residents of foreign countries, including U.S. citizens and legal residents. (Some of these occurred in the dissidents’ country of residence, others in third countries where the individual was traveling.)

Iranian operations frequently targeted Israeli interests, including 27 incidents in the overall dataset and at least 23 cases over the past decade. Still more disturbing, however, is the prevalence of Iranian external operations apparently targeting Jews, not Israelis. (In several incidents, the operatives were targeting both.) Iranian operatives and their proxies carried out surveillance or operations specifically targeting Jews in places such as Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Germany, India, Nepal, Nigeria, and the United States, including surveillance of Jewish cultural centers, synagogues, and tourists.

Overall, 24 Iranian assassination or attack plots targeted foreign diplomats or diplomatic compounds, including 19 incidents over the past decade. The targeted diplomats represented Israel, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and the United States. These plots primarily took place in countries with weaker security services, with the notable exceptions of surveillance operations in Israel and the 2011 Arbabsiar plot targeting the Saudi Ambassador to the United States (discussed below). One of the most disturbing of these plots, from an American perspective, was the 2011-2012 plot targeting specific U.S. diplomats and their families in Baku, Azerbaijan, among other targets.27

Over the past decade, 12 cases targeted Western interests in the West (the United States, Germany) or in other countries (Bosnia, Kenya, Israel, Colombia, Ethiopia, South Africa, Nigeria, Azerbaijan). Overall, Western interests were targeted in 24 cases.

Perpetrators of Iranian External Operations

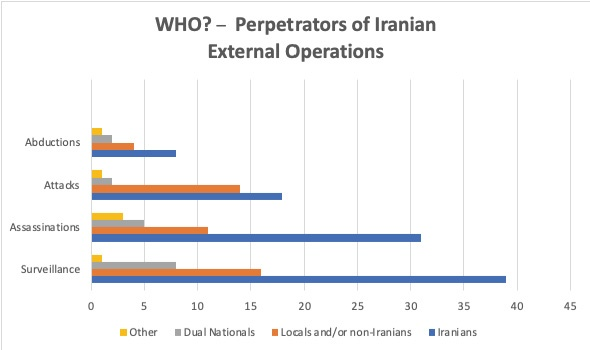

Over the years, Iran had deployed its own operatives—some affiliated with the Quds Force, others with the MOIS—to execute or help carry out international operations, often using diplomats or operatives acting under diplomatic cover—a phenomenon this author explored in detail in a 2018 article in this publication.28 Iranian diplomats or operatives with diplomatic cover were involved in at least 22 plots overall in the dataset, including 13 over the past decade.

The Assadi case stood out by nature of the plot itself (bombing a massive rally where American and other diplomats were present), but it was only the most recent example of Iranian state-sponsored terrorism in which Tehran has used visiting government officials or accredited diplomats to plot terrorist attacks. Iranian diplomats were deeply involved in the 1992 and 1994 bombings of the Israeli embassy and AMIA Jewish community center, respectively, in Buenos Aires, and have a long track record of just this kind of activity. In 1987, for example, a U.S. intelligence report noted that “Department 210 of the [Iranian] Foreign Ministry serves as a primary operations center for coordination with Iranian intelligence officers abroad, and is often used to instruct intelligence officers about terrorist operations.” The report continues, “The Revolutionary Guard, which is the principal agent of Iranian terrorism in Lebanon, uses its own resources as well as diplomatic and intelligence organizations, to support, sponsor, and conduct terrorist operations.”29

In an effort to carry out attacks with relative deniability, Iran has also deployed operatives who are dual nationals (typically citizens of Iran and another country, but sometimes of two countries other than Iran). Dual national operatives appear in 21 cases, including 15 just in the past decade, marking a significant shift toward this trend. Over the years, these have included citizens of Afghanistan, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Germany, Iraq, Lebanon, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Tunisia, Turkey, and the United States.

In 38 of the 98 cases in the dataset, non-Iranian citizens carried out the operations in question—24 of these were carried out in the last decade. Five of these non-Iranian perpetrators were dual nationals of other countries, but the remainder were nationals of one country. In 15 cases in the overall data set, the perpetrators were Hezbollah operatives engaged in Iranian operations.

Dual national and non-Iranian operatives would be expected to travel and operate using their non-Iranian travel documents, though in some cases they exhibited poor operational tradecraft and traveled on Iranian documents, used their true Iranian names, carried Iranian currency, used the same SIM card for operations in different countries, or allowed their pictures to be taken with local prostitutes, as discussed below. In some cases, they may have used Iranian travel documents to enter countries, like Malaysia, that do not require a visa for Iranian passport holders.

In a few cases, Iran outsourced some operational activities to criminal organizations, mostly in the past few years. In seven cases—six in the past decade—Iran contracted criminals to carry out surveillance or execute plots. As is often the case, working with criminals negatively affected operational security in some cases.

Iran relied on established proxy groups, like Hezbollah, to assist with some aspect of external operations in 20 cases, nine of which occurred since 2011. Prior to 2011, seven plots were carried out by Iran with assistance from proxies, while four were executed by proxies alone. Over the past decade, proxies carried out two plots on their own and played support roles alongside Iranian operatives in another seven.

WHAT? – Types of Iranian External Operations

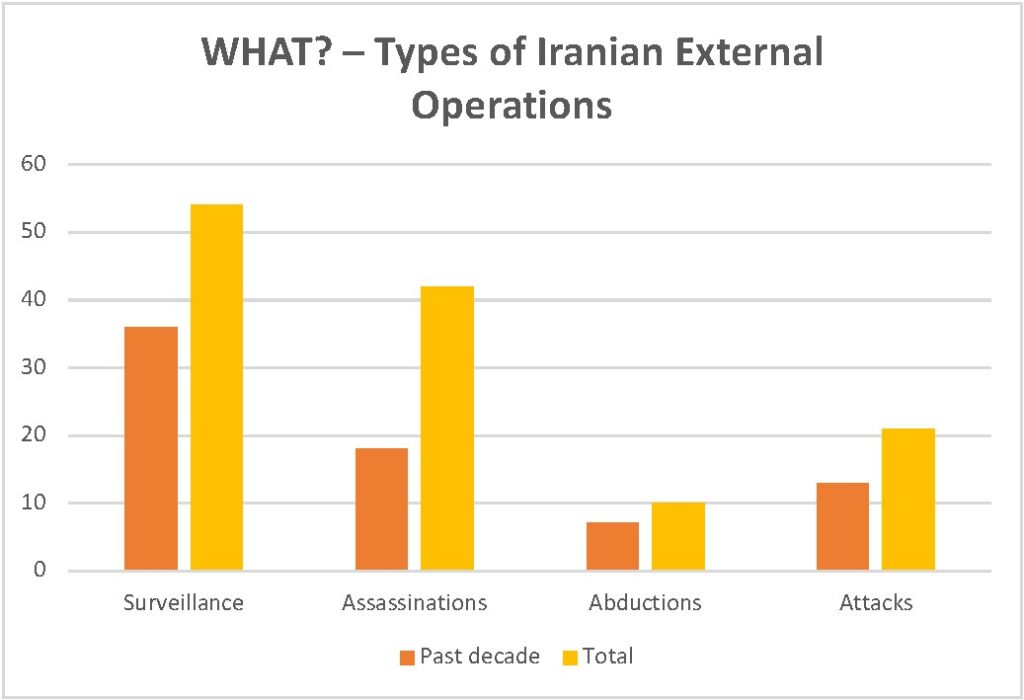

Iranian external operations examined in this study fall into four typologies: (1) targeted assassination plots; (2) abduction plots; (3) indiscriminate attack plots (i.e., bombings); and (4) surveillance operations in support of such plots.

The dataset includes 42 assassination plots, not all of which were successful. Of these, 18 occurred within the last decade. The assassination plots that occurred prior to 2011 were typically carried out by Iranian operatives (21 out of 24), but an analysis of the 18 cases executed over the past decade shows that over this more recent time period, Iran has been just as likely to dispatch locals or non-Iranians, dual nationals, or criminals as actual Iranian operatives.

This dataset includes 10 abduction plots, seven of which occurred since 2011. Iranian operatives were involved in all these plots, though three also used local, non-Iranian operatives. One recent plot, which targeted Iranian-American human rights activist Masih Alinejad in the New York area and was revealed in July 2021,30 displayed a combination of effective and outlandish tactics.

This dataset did not aim to include every indiscriminate attack tied to Iran and its proxies over the past several decades, but it included 21 key events (plots and attacks) with clear open-source evidence of Iranian involvement. While such attacks have been carried out at a steady pace over the past four decades, over the past decade Iran appears more willing to carry out assassination plots using more indiscriminate tactics such as bombings (consider the 2018 Paris plot targeting MEK and the 2011 Washington, D.C., plot targeting the Saudi Ambassador). In such plots, Iran typically deploys a combination of its own operatives and proxies to execute the attacks.

Each of these operation types typically involves some pre-operational surveillance, so it should not surprise that 54 cases in the dataset are listed or cross-listed as surveillance cases. Of these, 36 occurred in the past decade. Iranian operatives were typically involved in surveillance operations, often working together with proxies. Since 2011, surveillance operations appear to also include locals or non-Iranian operatives more frequently.

Over the past decade, a number of aggressive Iranian plots in the West have forced U.S. and European security experts to reconsider long-held assessments regarding the assumed limits of Iranian external operations. In the wake of the 2011 Arbabsiar plot, then-Director of National Intelligence James Clapper testified before Congress that the plot “shows that some Iranian officials—probably including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei—have changed their calculus and are now more willing to conduct an attack in the United States in response to real or perceived U.S. actions that threaten the regime.”31

A few years later, FBI agents arrested Hezbollah operatives Ali Kourani and Samer el-Debek in New York. Among other things, Kourani carried out surveillance of U.S. government agencies in New York and airports in New York and Toronto, while el-Debek surveilled U.S. and Israeli interests, as well as the Panama Canal Zone, in Panama. The arrests prompted the U.S. intelligence community to revisit its longstanding assessment that Hezbollah would be unlikely to attack the U.S. homeland unless the group perceived Washington to be taking action directly threating the existence of its patrons in Tehran. In a press conference following their arrest, the director of the U.S. National Counterterrorism Center said, “It’s our assessment that Hezbollah is determined to give itself a potential homeland option as a critical component of its terrorism playbook.”32 In a meeting with FBI agents, Kourani admitted to being a member of Hezbollah’s Islamic Jihad Organization terrorist wing (Unit 910), adding “the unit is Iranian-controlled.”33 He explained that although the unit reports directly to Hezbollah’s secretary-general, Hassan Nasrallah, Iran oversees its operations as well. Kourani informed the FBI that “there would be certain scenarios that would require action or conduct by those who belonged to the cell.” Kourani said that in the event that the United States and Iran went to war, the U.S.-based sleeper cell would expect to be called upon to act. And if the United States were to take certain unnamed actions targeting Hezbollah, Nasrallah himself, or Iranian interests, Kourani added, “in those scenarios the sleeper cell would also be triggered into action.”34

In January 2019, the European Union also revisited its assessments of Iranian terrorist activities abroad, designating the Directorate for Internal Security of the MOIS, along with two of its officials, after the Danish, Dutch, and French governments accused it of carrying out assassination plots in Europe.35 The Danish foreign minister said the “EU just agreed to enact sanctions against an Iranian Intelligence Service for its assassination plots on European soil,” calling the action a “strong signal from the EU that we will not accept such behavior in Europe.”36

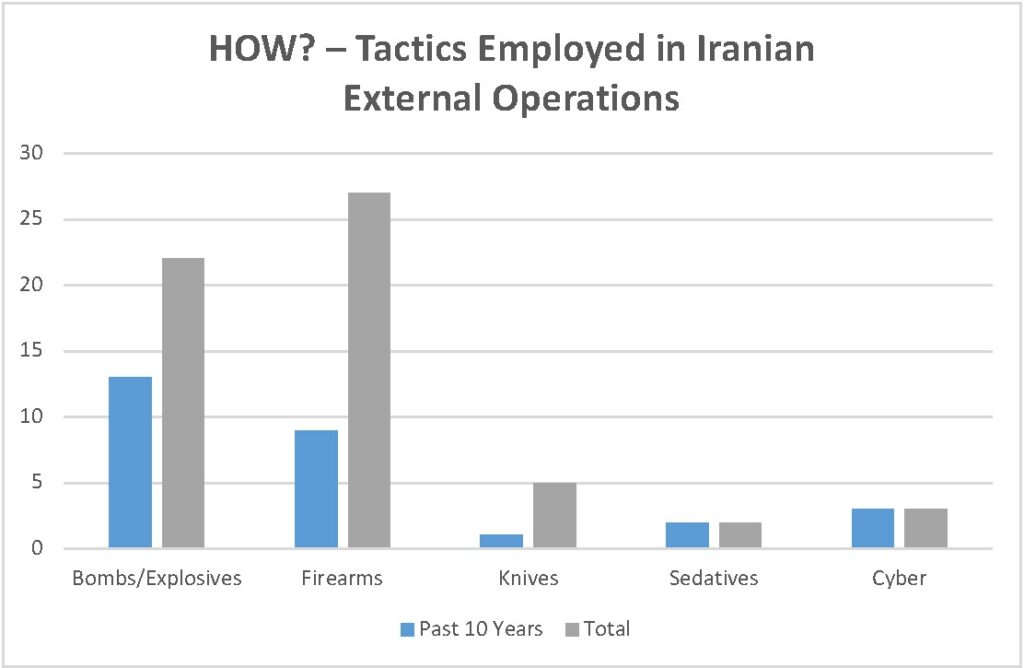

HOW? – Tactics Employed in Iranian External Operations

Iranian external operations have featured a variety of tactics and weapons. A few Iranian plots involved knives—and in one case, an operative considered running over a California-based Iranian dissident with a car37—but most cases involved small arms or explosives. Bombs have become somewhat more common in cases over the past decade, and in recent years, there have been a couple of abduction cases involving sedatives.38

But the most significant development over the past few years has been the use of cyber tools for surveillance and targeting. For example, in 2019, the U.S. Treasury targeted an Iranian organization that hosted conferences in cooperation with the IRGC-Quds Force to serve as recruitment and intelligence collection platforms. Conference organizers specifically facilitated contact between Quds Force personnel and U.S. persons.39 In 2012, Monica Witt, a former U.S. Air Force intelligence specialist, allegedly attended one of these conferences in Iran and was recruited by Iranian intelligence. The Department of Justice indicted Witt in 2019, alleging that part of her work involved researching USIC personnel she had known and worked with and using that information to put together “target packages” on them.40 Witt remains a wanted fugitive and features on the FBI’s Most Wanted list.41 The U.S. Treasury Department targeted an Iran-based cyber company that worked with the IRGC and MOIS and ran a cyber operation to gain access to the computer systems of current and former U.S. counterintelligence agents and implant malware on their computer systems.42

A review of travel patterns in Iranian external operations reveals several cases in which operatives used false passports, including six in the past decade. Interestingly, Iranian agents have been caught using forged Israeli passports (as have Iranians who appear to have been economic migrants). The use of dual nationals traveling on their non-Iranian passports is an important and current modus operandi.

The dataset includes a wide variety of financial activities, including money laundering to pay a private investigator for work related to an abduction plot in the United States.43 In other cases, agents carried a few thousand dollars in cash on their person to pay local agents,44 an Iranian intelligence agent with diplomatic cover was found with 30,000 euros in Europe,45 Iranian students were paid to study abroad to collect intelligence,46 and dual citizens living abroad were promised as much as $1 million to carry out surveillance missions.47 In one case, an Iranian was paid $300,000 to abduct an Iranian dissident,48 and a Shi`a imam in Africa was paid around $24,000 to carry out surveillance in Nigeria.49 In Baku, Azerbaijan, members of a crime gang were reportedly paid $150,000 each to target a Jewish school there,50 and Arbabsiar sent tens of thousands of dollars in two wire transfers from an overseas bank account to hire someone he believed to be an assassin.

According to a report produced by the Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress, the MOIS has overall responsibility for covert Iranian operations, but since its founding in 1990, the Quds Force has typically carried out extraterritorial operations like assassinations:

According to Iran’s constitution, all organizations must share information with the Ministry of Intelligence and Security. The ministry oversees all covert operations. It usually executes internal operations itself, but the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps for the most part handles extraterritorial operations such as sabotage, assassinations, and espionage. Although the Quds Force operates independently, it shares the information it collects with MOIS.52

Over time, the Library of Congress study reports, a division of labor developed between the MOIS and Quds Force regarding international operations. The “MOIS has mostly concentrated on monitoring and assassinating Iranian dissidents inside and outside of the country,” while “the Qods Force is in charge of covert military and paramilitary actions outside of Iran’s territory, including the assassination of foreign individuals, such as Israeli officials, as well as training of militant groups and gathering of information in regions of interest to Iran.”53

Typically well-trained, Iranian operatives have demonstrated skillful tradecraft in some cases, but they are not 10 feet tall. To the contrary, Iranian agents have shown exceptionally poor judgment and disregarded basic operational security in other cases. Over several months in 2012, Iranian operatives planned what one investigator described as a “jumble of overlapping plots,” including assassinating U.S. diplomats and a local rabbi or striking other Jewish targets.54 In Thailand, police rushed to the scene of an explosion at a home rented by a group of Iranians. Two barefoot men fled the house, but a third was injured and tried to hail a taxi to escape. When the taxi refused to stop, the injured man threw a bomb at the car, destroying half the vehicle and injuring the driver and four bystanders. Police soon cornered the injured suspect, who tried to throw another explosive at them but was too weak; the resulting explosion blew off both his legs.55 In this and a series of other operations, Iranian agents reused phone numbers and SIM cards across multiple operations, traveled on Iranian passports, checked in to hotels as Iranians, carried Iranian currency in their wallets, and in at least one instance, took off time from their surveillance to party with prostitutes. A group photo on the cell phone of one of the prostitutes helped identify accomplices, one of whom was arrested at the airport while the other managed to escape.56

A trove of leaked Iranian intelligence cables obtained by The New York Times and The Intercept in 2019 underscores this point. The so-called Iran Cables reveal both sophisticated tradecraft and successful operations—including the purported recruitment of a U.S. State Department employee as a source. “By and large,” The New York Times assessed, “the intelligence ministry operatives portrayed in the documents appear patient, professional, and pragmatic.” And yet, the cables also include cases of “bumbling and comical ineptitude” on the part of Iranian agents in Iraq.57

These leaked Iranian cables also underscore how internal Iranian politics, competing factions, and interagency rivalries sometimes significantly undermine Iranian tactical capabilities. For example, the MOIS is a very capable organization, but in recent years, it has sometimes been overshadowed by the IRGC and the fairly new IRGC Intelligence Organization, formally established only in 2009 in the wake of the failed “Green Revolution.”58 Several rounds of purges within the MOIS aimed at ridding the ministry of people perceived to be supporters of reformist presidential candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi, partially explaining why the MOIS appears to have fallen in standing in the eyes of Iranian revolutionary leaders compared to the Quds Force.59 The revolutionary leadership appears to have suspected that at least some within the MOIS sympathized with leaders of the Green Movement opposition. The resulting intelligence reorganization reportedly purged the MOIS of hundreds of officials. “This solidified the IRGC’s control of Iran’s intelligence apparatus and weakened the government’s ability to challenge the IRGC’s authority and to impede its activities in cracking down on dissenters.”60 Today, senior IRGC officers fill key ambassadorial positions in the Middle East, and with the election of President Raisi, the IRGC is likely to grow more powerful still.61

WHERE? – Locations of Iranian External Operations

Iranian agents and their proxies have carried out many operations over the years in places with relatively lax security and border controls, where Iranian influence could secure the release of detained operatives in the case of arrest. They have also focused on places where Iranians can travel without a visa such as Malaysia.

In the post-9/11 world, overall border security enhancements in countries around the world likely led terrorist groups and rogue actors of all kinds to either curtail operations for a period of time and/or operate in nations with comparatively lax security rather than more vigilant Western nations. The dataset suggests there was a gap in Iranian external operational activity for about 23 months after 9/11, and the operations that commenced after that time in the West were all surveillance operations, which may not have been tied to near-term plots but rather were contingency planning for future off-the-shelf operational planning.

Over time, however, Iranian operatives and proxies resumed a wide array of international operations in both Western countries and those with less developed security systems. After a post 9/11-hiatus, plots in the United States increased (seven in the decade after 9/11,62 and seven more in the decade since 201163), while there were only two plots in Europe in the decade after 9/11.64 This dramatic drop in attacks in Europe reversed itself over the past decade, however, with 17 plots in Europe since 2011.

Of the 20 cases in which Iranian operatives and proxies targeted U.S. interests, 12 occurred outside the United States in countries with more lax security systems. These most frequently took place in Central Asia, the Gulf, and Africa, but also in other places like Eastern Europe.

Similarly, in several cases in recent years Iranian agents targeted dissidents living in the West while they traveled to third countries. For example, a dissident living in Sweden was targeted in Turkey,65 a dissident in the United States was targeted in the UAE,66 and a dissident in France was targeted in Iraq.67 Israeli targets (distinct from Jewish targets) were also primarily targeted in third countries.

Effective security measures have also influenced Iranian agents’ target selection within countries. For example, on February 13, 2012, twin bombings targeted personnel from the Israeli embassies in New Delhi, India, and Tbilisi, Georgia. In each of these cases, Quds Force operatives encountered more sophisticated security arrangements than anticipated, and so they settled for modest strikes.68

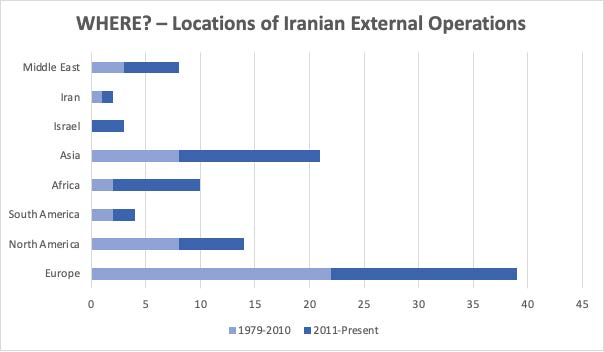

And yet, Iranian operatives have also carried out plots in Western countries with sophisticated law enforcement and intelligence services, including the United Kingdom and the United States. Fifty-three cases in the dataset occurred in North America (14) or Europe (39), while 43 occurred in South America (four), Africa (10), Asia (21),a and the Middle East (eight). New York and London were frequent locations for operations (eight and six, respectively), and there has been a distinct focus on plotting attacks in the Gulf over the past decade.

Ultimately, the reason Iran targets dissidents and others in one country over another may have as much to do with opportunity—access to the target, agents capable of operating in a specific location—as anything else.

WHEN and WHY? – Examining Motives for Iranian External Operations

Discerning motives for specific Iranian external operations is a tricky business. In some cases, such as Iranian sticky bomb plots in 2012,b motive can be rather clear. In that case, Iran was striking back after attacks on its nuclear program, including assassinations of key nuclear scientists, and deterring future attacks.69 These attacks were carried out by Quds Force Unit 400, which was set up for this specific purpose.70 Or consider that, according to a declassified July 1992 CIA report, Hezbollah began preparing retaliatory attacks against both the United States and Israel shortly after an Israeli airstrike killed then-Hezbollah leader Abbas al-Musawi in February 1992.71 Most accounts tie the March 1992 bombing of the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires to these events.

In other cases, the attack was proposed and the planning begun before the supposedly precipitant event. Consider, for example, the 1994 bombing of the AMIA Jewish Community Center in Buenos Aires. That attack is often tied to the May 1994 capture of Iranian-affiliated Shi`a militant Mustafa Dirani in an Israeli commando raid in Lebanon. But while the Dirani affair certainly gave Iran and Hezbollah reason to carry out a retaliatory attack, the AMIA bombing was more than a year into the planning stages by the time Dirani was snatched.73 More recently, the 2012 sticky bomb attacks were reportedly planned to take place close to the February 8 anniversary of the assassination of Hezbollah’s Imad Mughniyeh. In other words, once they were planned anyway, why not take advantage of the symbolic date?74

There are also theories that make sense but cannot be conclusively verified using open-source data alone. Consider the case of Iranian-American used car salesman Mansour Arbabsiar who pleaded guilty in 2012 to plotting with Iranian agents to assassinate the Saudi ambassador to the United States in Washington, D.C. The actual precipitant for this plot remains unclear, but there are some theories. According to one theory, it was the crackdown on the 2011 “Arab Spring” protests in Bahrain that perhaps pushed Iranian security and intelligence services toward a new level of militancy. The deployment of Bahraini Defense Force tanks, backed by Saudi Arabian and UAE forces, caused shock and anger among Bahraini Shia and among the Shia leadership and people of Iran and of Iraq.75 There is some indication that the Iranian leaders regretted not being in a position to support the Bahraini Shia in what might have been a decisive political action against the Sunni monarchy.76 It was reportedly right after the 2011 protests that Arbabsiar presented himself to his cousin, a senior Quds Force official, and that the Quds Force began planning the assassination of the Saudi ambassador, Adel al-Jubeir. Gholam Shakuri, the IRGC-Quds Force officer identified by one of the plotters as being in charge of the operation, is believed by Saudi intelligence to have met with a radical Bahraini Shia cleric in Beirut in early 2011 before the operation began.

Understanding when and why Iran and its proxies carry out attacks is further complicated by the fact that they do not always coordinate their activities and sometimes appear at cross-purposes for failure to deconflict their operations. So, while the Quds Force, Iran, and its primary proxy group, Hezbollah, have worked together on some plots—Baku in 2012c and Istanbul in 2011,d among others—in other cases, they failed to deconflict their operational activities and found themselves engaged in completely disparate operations in the same place. When Hezbollah operatives laid the groundwork for a bombing plot in Bangkok in late 2011 and early 2012, the group was apparently unaware that the Quds Force was also preparing for an attack in the same city.78 Whether the Quds Force was, in turn, ignorant of Hezbollah’s activities there is unclear, but the Iranians appear not to have known Hezbollah was using Bangkok as an explosives distribution hub. And even after Hezbollah operative Hussein Atris was arrested in January 2012, the Quds Force operation there was not suspended.79 Similarly, within days after the July 2012 bombing of a bus carrying Israeli tourists in Burgas, Bulgaria—even as the international and very public investigation into the bombing and the search for accomplices was at its height—Bulgarian authorities reportedly caught a Quds Force operative scoping out a synagogue in the country’s capital, Sofia.80

Iranian operatives have at times been so driven to carry out an attack that they have rushed operations that were not yet ready. In 2012, for example, when the Quds Force established Unit 400 to strike back at countries undermining Iran’s nuclear program, the desire to carry out an attack outpaced the new unit’s actual capacity to do so.e The fact that Iran’s intentions were not yet coupled with the capability to act effectively on them gave Western officials only so much comfort. In time, they feared the Quds Force would be capable of carrying out deadly attacks targeting Western interests.81 The pace of Unit 400’s planned attacks underscored just how determined Iran was to attack Western interests. Yet the failure of all these plots pointed to the new unit’s still-limited capabilities.

Iranian officials also seem to reward initiative, even aggressive initiatives that are not necessarily sanctioned in advance or ultimately successful. By some accounts, that explains the 2007 detention of British Royal Navy personnel in the Persian Gulf.82 Moreover, internal bureaucratic tensions within the parallel and sometimes overlapping elements of the Iranian security establishment can also lead to a form of competition that breeds adventurism and may affect Iranian international operations.

Decision-making and operational planning within the Iranian system is opaque. In some cases, officials have definitively linked a plot back to senior Iranian officials. In the Arbabsiar plot, for example, U.S. and British governments traced the conspiracy back to its source in Tehran and blacklisted Quds Force commander Qassem Soleimani for his role overseeing the plot.83 Indeed, with U.S. law enforcement officials listening in, Arbabsiar called his cousin and Quds Force handler, Gholam Shakuri, asking if the plan to blow up a popular Washington, D.C., restaurant should go ahead. Shakuri confirmed that the plot should go forward and as soon as possible, adding, “Just do it quickly. It’s late.”84 But for many cases that do not end with a trial or declassified intelligence to support a statement or U.S. Treasury designation, open-source attribution to senior Iranian officials can be difficult to make.

There are a few general themes, however, that help contextualize Iranian external operations.

Iran seeks to undermine and target dissident groups that the revolutionary regime perceives to threaten regime stability. This includes groups accused of carrying out attacks in Iran, such as the Arab Struggle Movement of the Liberation of Ahwaz (ASMLA), and groups that reveal sensitive information about Iran’s nuclear program, corruption, or other sensitive matters, such as the NCRI.

Iran seeks to exact revenge for real and perceived acts of aggression against its interests, which is intended to exact a cost for such activities and deter future incidents. This is the case even when the act targeting Iran is carried out to thwart Iranian malign behavior of some kind.

Iran’s antipathy toward Israel and its commitment to the destruction of the Jewish state is real, though most typically pursued through proxies. Iranian external operations have targeted not only Israeli diplomats, citizens, and interests, but also Jewish targets with no ties to the state of Israel.

Iran has, from time to time, carried out operations tied to its self-perceived status as the standard-bearer for revolutionary Islam.85 Iran has for decades competed with Saudi Arabia to be seen as the leader of the Islamic world, and it sees itself as the guardian of oppressed Muslims anywhere.

Acting through proxies in ways that are either reasonably deniable or at least one step removed, Iran manages risk and projects influence well beyond its borders.86 And when carrying out acts of violence, Iranian leaders do appear to apply their own sense of proportionality and reciprocity. (So, a country that hosts the MEK, for example, should not be surprised if Iran targets MEK interests there.) Iranian use of violence is calculated, often as focused on the psychological effects of an operation as the operation itself.

Forecasting Possible Future Trends in Iranian External Operations

The election of Ebrahim Raisi—a loyalist and former student of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei—as president of Iran represents a significant step in the solidification of the IRGC’s place at the center of Iranian power and decision-making. Under his presidency, the IRGC is likely to be expanded and empowered in advance of the day when the Islamic Republic needs to select Khamenei’s successor. As a Tony Blair Institute for Global Change report concludes, for Khamenei and Raisi, “the IRGC will play a vital role in smoothing the transition to the next supreme leader.”88 An empowered IRGC will likely be still more aggressive in its efforts to protect the revolution, increasing the likelihood that international targeted assassination, abduction, and surveillance plots, as well as indiscriminate attacks, will continue to be a feature of Iranian operations abroad and may well become more common. In the eyes of Iranian leaders, such plots are a proportionate and reasonable response to support for Iranian dissident groups. As then-Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif retorted after the European Union accused Iran of carrying out assassinations in European countries, “Accusing Iran won’t absolve Europe of responsibility for harboring terrorists … Europeans, incl(uding) Denmark, Holland and France, harbor MEK.”89 And absent a renegotiated Iran Deal, with sanctions denying Iran reintegration into the international financial system, Iran will likely resort to what it considers to be reasonably deniable but proportionate attacks on those seeking to undermine the revolutionary regime in Iran.

Based on the findings of the data collected for this study, there is likely to be significant continuity in Iranian external operational activities. As noted above, Iran has begun to deploy cyber capabilities from its toolkit, typically to spy on dissidents, conduct electronic surveillance, and engage in disinformation campaigns. But as the cases involving this emerging cyber capability demonstrate, Iran and its proxies do learn and develop new tactics. The most significant tactical shift that could come in the months and years ahead involves the deployment of teams of Shi`a militants from around the world—mostly non-Iranian and non-Lebanese—representing a variety of Iranian proxy groups to carry out operations at Iran’s behest.90 As this dataset makes clear, both Hezbollah and the Quds Force have deployed dual-national operatives traveling on their non-Iranian passports.91

Perhaps the most important finding to emerge from this study is the fact that Iran pursues international assassination, abduction, terror, and surveillance plots in a very aggressive fashion, even at times and in places that are particularly sensitive. With the exception of a period right after the 9/11 attacks, when Iran did not want to get caught up in the “war on terror,” Iranian operatives and proxies have carried out operations even during periods of key negotiations—including current negotiations over a return to the JCPOA.f Iranian operatives and proxies carried out plots in Europe even as Iran sought to garner European support for its negotiating positions regarding the nuclear deal.g Today, with the revolutionary leadership solidifying control over key elements of power in Iran, and with an eye toward protecting the revolution at a time when the revolutionary leadership sees increasing threat coming from elements both foreign and domestic, operations like these are likely to increase.

The findings presented in this article underscore that the global response to Iran’s international terrorist activity cannot be limited to law enforcement action alone. It should include regulatory action, including expanding the E.U. designation of just Hezbollah’s military wing to include the organization in its entirety, as well as expanded financial and diplomatic sanctions targeting Iranian actors and institutions involved in these plots. But financial sanctions alone are insufficient and indeed are only truly effective when implemented in tandem with other tools. Western states should designate more Iranian institutions and personnel involved in Tehran’s illicit conduct, but they should also ensure that Iran faces consequences, including diplomatic isolation, for abusing diplomatic privilege and sending its representatives abroad to participate in attacks and assassinations on foreign soil.

The only real precedent for such action—and a poor one at that—is what followed the 1997 German court ruling that found Iran to be behind the 1992 attack at the Mykonos restaurant in Berlin.h Several European countries briefly withdrew their ambassadors from Iran following the court’s finding that Iranian officials were directly involved in the attack. But none of the Iranian leaders implicated in the plot were brought to justice, and several—most notably, Ali Akbar Velayati—went on to play roles in subsequent terrorist plots.92 Despite repeated Argentinean requests for countries to arrest and extradite Velayati as he traveled the world, he remains free.93

Following the more recent Assadi affair, the State Department published timelines and maps documenting open-source incidents of Iran-sponsored operational activities, by both Iranian agents and Iran’s proxy, Hezbollah, in Europe from 1979 to 2018.94 Documenting such plots is important not only to keep an accurate, factual record of Iranian operations but also so they can be put to use as evidence in diplomatic efforts to isolate Iran for its malign activities.

Iran continues to engage in such activities because it can. Experience has taught Iran that the benefits of such actions (as Iran perceives them) outweigh the few and typically temporary consequences. Law enforcement action and financial designations are appropriate but insufficient responses to such activities. They should be complemented by firm diplomatic isolation, travel bans preventing family members of Iranian leaders from studying abroad or going on European shopping sprees, and other actions that would feel truly consequential for Iranian decision makers.